- Slug: BC-CNS-Opioids Disposal,1750

- Photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

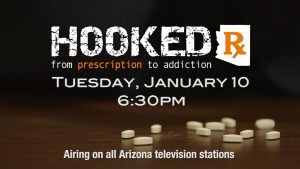

- EDS: PLEASE RUN THE HOOKED PROMO PHOTO (below) OR THIS BOX WITH THIS STORY IF YOU PLAN TO PUBLISH PRIOR TO JAN. 10: Watch “Hooked Rx: From Prescription to Addiction,” a 30-minute commercial-free investigative report airing at 6:30 p.m. on Jan. 10 on 30 broadcast TV stations in Phoenix, Tucson and Yuma and 97 of the state’s radio stations. For the full report, go to hookedrx.com.

By JOSHUA BOWLING

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – Doctors dole out millions of prescriptions for powerful painkillers – from oxycodone to fentanyl – every year in Arizona. Thousands of pounds go unused.

State and local officials have worked to convince both consumers and those in the medical field to turn in these leftover narcotics to a designated source so they can dispose of them the safest way: incineration.

Turning them in also helps keep these drugs out of the wrong hands. Arizona faces a growing opioid epidemic: In 2015, more than 400 people died in the state from an overdose of prescription pain relievers, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services.

On the consumer side, state and local officials have held numerous “take-back” events, set up drop-off locations at police stations and pharmacies across the state, and issued guidelines to the public on how to safely dispose of their medications. Residents turned in more than 12,000 pounds of drugs at a Drug Enforcement Administration take-back event in April.

“It’s working,” said Dr. Keith Boesen, director of the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center. “Arizona, I think, is fairly aggressive and unique in really wanting to address this problem.”

Yet, many consumers still toss unused medications in the trash or flush them down the toilet, where they could end up polluting the water supply. Some pharmacies and health care facilities have medication that slips through the cracks, and workers face penalties for diverting the drugs, where they could land in the hands of abusers.

Nobody really knows how many drugs aren’t disposed of properly. But a 2014 report from the Senate Environmental Quality Committee in California suggested hundreds of millions of pounds of prescriptions are flushed nationwide.

“A 2004 patient survey revealed that only 2 percent used all medication prior to expiration, and that 90 percent disposed of their medications in the trash, toilet, or sink,” the report said. “Most estimates suggest that 3 to 50 percent of prescriptions become waste.”

Officer Joe Bruno of the Phoenix Police Department said the Mountain View Precinct, near 20th Street and Maryland Avenue, takes back large quantities of drugs. Although the department designates bins specifically for prescription drugs, Bruno said people drop off anything and everything – even if the bin’s labeling explains banned substances.

“Anything you can think of is thrown in there,” Bruno said. That includes liquid cough syrup, syringes and even multivitamins.

The department has taken steps to cut back on the amount of improperly disposed prescriptions for several reasons.

“We offer this to make sure we cut back the amount of narcotics out there, especially right now with teen use,” Sgt. Mercedes Fortune said. “We’re trying to minimize that, obviously. We also partnered up with the water department to make sure that those drugs do not go into the water system as well.”

Consumers

It has taken some effort to educate the public about proper disposal methods.

Boesen said part of the problem is that consumers for years couldn’t return unwanted drugs to pharmacies.

Instead, people keep the pharmaceuticals in their medicine cabinets just in case they need them in the future, especially hard-to-get pain medications.

“We don’t want these hoarded. We do not want them collecting dust in your cabinet,” Boesen said. “It’s kind of the 1950s attitude that liquor cabinets used to have a lock on them. Well, medicine cabinets need a lock on them.”

The take-back programs have proven popular.

Phoenix police say more people are making use of the program. Bruno and his colleagues are required to empty the drop-off bins once every month. However, they empty the bins about once every week because they receive too many medications to keep up.

“There’s a million ways that you can get rid of those things now,” said Doug Coleman, the special agent in charge of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Phoenix division. “We’re taking back tons and tons and tons of these things every time we do a take-back event. But I think that there’s still some people that are holding onto them.”

Coleman said they have held the take-back events in Arizona for five years and have brought in 72 tons of drugs. After the DEA collects drugs, agents send them to a third-party contractor for incineration. Coleman said the incinerators must meet U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulations.

Now, consumers have another option.

In September, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey announced a Walgreens take-back initiative for Arizona. Walgreens spokesman Phil Caruso said the pharmacy chain has launched this program across the nation, and Arizona is one of the most recent states to implement it.

Anyone who wants to drop off expired or unwanted prescriptions can do so at 18 Walgreens in 12 Arizona cities.

Boesen said that while officials have worked hard to educate the public about proper drug disposal – including warnings on water bills, hosting educational events, setting up websites – they have more work to do.

“Where some of it is lacking is funding to do, say, bigger advertisements – whether it’s TV, radio, billboards, what have you,” he said. “There’s not a lot of funding right now to get the word out.”

Pharmacists

The state also has implemented tougher regulations for the health community and tried to create more awareness among professionals about the opioid epidemic.

According to the Arizona State Board of Pharmacy in a 2013 Prescription Drug Misuse and Abuse Initiative, pharmacists have a checklist to follow before disposing of medication:

● Keep a monthly log of medication ready for destruction.

● Make sure medication is recorded, stored and destroyed in accordance with federal DEA regulations.

● Be open to random DEA inspections of the pharmacy’s prescriptions.

Coleman said his office investigates prescribers and pharmacists, who have to register with the DEA, and makes sure they’re maintaining safe prescribing and disposal habits.

“I know exactly how many pills were purchased by that pharmacy from Purdue Pharma or from McKesson or from Pfizer,” Coleman said. “I know exactly how many pills because Pfizer has to report that to me. So I go in with my report from Pfizer and I go, ‘OK, Pharmacy 1, Pfizer says they’ve sent you 900 pills, 900 Oxys, I want to look and see where your 900 Oxys went.’”

However, prescribers and pharmacists ultimately report to the Arizona State Board of Pharmacy. The DEA sets federal regulations overseeing prescriptions and their disposal, while the state pharmacy board enforces those regulations.

The pharmacy board is comprised almost entirely by pharmacists – leaving pharmacists to oversee pharmacists.

If the DEA is tipped off to a pharmacist who isn’t properly disposing prescriptions, the pharmacy board can discipline that pharmacist. Discipline could range from a slap on the wrist to a license removal.

For example, the pharmacy board in 2011 caught a pharmacist out of Anthem diverting substances for personal use, according to Arizona State Board of Pharmacy records. Robin O’Nele’s pharmacy was short 6,254 pills, according to the report. Nearly 1,000 pills of hydrocodone, an opioid, were among the missing medication.

Records show O’Nele admitted to taking her own anti-fungal and pink eye medications, but the audit did not state who was responsible for the missing opioids.

In November, the board disciplined O’Nele a second time. Her 2011 consent agreement subjected her to monitoring by the board for five years. In May, O’Nele underwent a random drug screening and its results in June showed she tested positive for opioids – specifically codeine and morphine.

Records show O’Nele said she tested positive because she took a mix of Tylenol and codeine prescribed to her son to alleviate the pain of what she believed to be a kidney stone.

The pharmacy board originally suspended her license and ordered her to complete 400 hours of community service. The board has since extended her probation an additional five years.

Now that some pharmacies have installed drop-off boxes, they face tighter scrutiny on the drugs they bring in.

Pharmacies have to register with the DEA before they can have a take-back program. The DEA and pharmacy board must ensure that pharmacists keep accurate books and don’t skim any of the medication designated for destruction.

“If there’s any wrongdoings, obviously the DEA and my agency would work together to do an investigation and see if there’s any wrongdoing,” said Kam Gandhi, executive director of the Arizona State Board of Pharmacy.

Hospitals and emergency rooms also have pharmacies on site to dispense medication. Should someone die in hospital care with an active prescription, the hospital pharmacy must dispose of the medication.

The pharmacy contracts with a third party to bring the pills to an incineration site.

Alternatives

Arizona now has about 120 drop-off locations, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services.

But there are gaps, Boesen said.

“Everyone doesn’t live a few steps away from a drop box,” he said.

Boesen said there are some private companies that accept medications by mail. These private companies specialize in medical waste and will incinerate the narcotics, he said. According to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, some companies do offer mail-back programs for disposing of prescriptions. Dropping the drugs off at a designated drop-off location is more common, however.

There are some problems. Many of these takeback programs won’t accept liquids. And only a handful of companies are certified by the EPA to incinerate these drugs, so it’s expensive.

For those who can’t get to a drop box, the EPA also has proposed guidelines for consumers who want to get rid of the leftover drugs but can’t get to a drop box:

“Dispose in household trash, after mixing the unwanted medicines with an undesirable substance such as kitty litter or coffee grounds and placing in a sealed container,” the proposed rule reads. “Only if the drug label specifically instructs you to, flush the unwanted medicine down the toilet.”

Although flushing drugs is discouraged and would introduce drugs into the water system, EPA research acknowledges the uncertainty of any side effects.

“There are so many chemicals in our water samples today because a lot of drugs that we ingest pass through us and they enter the water system through our body waste,” Gandhi said. “And if we’re just flushing those things down, we’re actually putting the pure drug into our water system.”

^__=