- Slug: BC-CNS-Opioids Rehabilitation Industry,2,300

- Photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

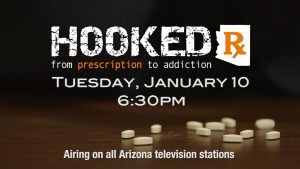

- EDS: PLEASE RUN THE HOOKED PROMO PHOTO (below) OR THIS BOX WITH THIS STORY IF YOU PLAN TO PUBLISH PRIOR TO JAN. 10: Watch “Hooked Rx: From Prescription to Addiction,” a 30-minute commercial-free investigative report airing at 6:30 p.m. on Jan. 10 on 30 broadcast TV stations in Phoenix, Tucson and Yuma and 97 of the state’s radio stations. For the full report, go to hookedrx.com.

By COURTNEY COLUMBUS

Cronkite News

TUCSON – At 19, Joey Romeo had his wisdom teeth removed.

His doctor prescribed 180 pills of hydromorphone, an opioid, to relieve the pain. That triggered a cascade of events that would take him in and out of more than 10 addiction treatment programs in two states.

Romeo, now 25, had tried prescription drugs before. But his mother, Susan Romeo, said after the 180-pill prescription, “There was no going back. He was 100 percent addicted.”

Romeo and his family have accumulated hundreds of thousands of dollars in bills trying to get him off – and keep him off – the pills. His parents have paid insurance copays for Joey’s time at addiction treatment centers. They have paid for stays in sober living homes. And they have paid Joey’s bills while he looks for jobs.

Susan keeps a crate full of the bills, pulling out stacks of them and piling them on the dining room table in her Tucson home.

“I don’t even count it. I would cry,” Susan said. “If I added up all the numbers, I’d probably be beside myself because I don’t want to think about it.”

Cronkite News conducted a four-month investigation into the rise of prescription opioid abuse in Arizona. Dozens of journalists at Arizona State University examined thousands of records and traveled across the state to interview addicts, law enforcement, public officials and health care experts. The goal: uncover the root of the epidemic, explain the ramifications and provide solutions.

Since 2010, more than 3,600 people have overdosed and died from opioids in Arizona. In 2015, the dead numbered 701 – the highest of any year before, or nearly two per day, according to an analysis by the Arizona Department of Health Services.

As the opioid epidemic continues to affect more Americans every year, the substance-abuse treatment industry has grown to keep up with demand. Americans spent $34 billion on substance use disorder treatment in 2014, up from $9 billion in 1986, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a Maryland-based federal agency that aims to improve behavioral health.

It’s difficult to determine the exact number of facilities that provide opioid-addiction treatment in Arizona because the state has varying degrees of regulation. For example, state officials don’t track unlicensed facilities, such as sober living homes, which don’t provide medical treatment. However, there are at least 650 licensed treatment providers in the state.

Those within the industry say they’ve noticed new rehab centers opening in Arizona. Not only are more people becoming addicted, the powerful effect of opioids on the brain makes it common for recovering addicts to relapse – meaning more time in rehab centers and more money out the door.

Experts say the high cost at some facilities, wait lists for centers that accept state-funded health plans, differences in quality of care and a complicated mix of treatment options mean it’s often difficult for addicts in Arizona to access effective care.

Angie Geren, executive director of the nonprofit Addiction Haven and a clinician at a Community Medical Services methadone clinic in Phoenix, helps to guide the families of recovering addicts through the treatment center system.

“Our treatment industry is so splintered. It’s so hard for parents,” she said. “No one has a road map of where to go.”

Industry growth

Since 1999, the amount of opioids prescribed by doctors in the U.S. nearly quadrupled, but the overall amount of pain reported stayed the same, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Given the scope of the epidemic, you only have about 20 percent of opioid-addicted people in treatment,” said Mark Parrino of the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence, a New York-based organization founded in 1984 that works to increase access to opioid treatment programs.

Still, the number of patients the group says has received care at opioid treatment programs has grown by 75,000 in the past 10 years.

Access to these centers varies across states and between urban and rural locations and often depends on each state’s laws and available public funding.

IBISWorld, an industry research firm, estimated the mental health and substance abuse industry would continue to grow during the next five years because of rising incomes and better insurance coverage.

And, opioid addicts tend to relapse several times.

Jeff Wondoloski, a therapist at Valley Hope of Chandler, said it can be especially easy for youth to relapse.

“When you take them off drugs, when you help them get sober, what happens is they pick up where they left off when they started using,” he said. “So you have someone who’s 24 who has the maturation of a 13, 14 year old. They’re lost, you know. There isn’t a whole lot of programs that are helping those individuals long term.”

He said the youth he works with tend to go through treatment more times than people in their 40s or 50s.

“You hear these young people talking about – almost bragging about – how many treatment centers they’ve been to, how many overdoses they’ve had, how many times they’ve had to get (opiate antidote) Narcan,” Wondoloski said. “You know, it’s like this badge of honor almost, and that’s sad.”

The substance abuse administration estimates that about two thirds of the money spent on treatment in 2014 came from public funds, while the remaining $11 billion was private spending.

Fair Health, a national nonprofit group, analyzed the costs of opioid abuse and dependence treatment. It found the number of private insurance claims submitted for opiate dependence had skyrocketed 3,200 percent from 2007 to 2014.

Cost of treatment

Treatment options in Arizona range from residential, 12-step approaches to maintenance doses of methadone and counseling at outpatient clinics. There’s a huge disparity in the costs of these programs.

One Phoenix-based nonprofit sober living home, 5A, charges residents a little more than $400 per month, including meals, and asks residents to commit to staying for three months.

A month of treatment at an in-patient center that incorporates the sometimes-controversial medicines methadone or buprenorphine into their treatment plans could cost an addict – or, in some cases, an addict’s family – more than 30 times as much.

Thirty days of inpatient treatment at the nonprofit center Valley Hope of Chandler costs $15,500 – more than $500 per day. Treatment centers that market themselves as “luxury,” with features such as equine therapy and rock climbing, could cost $40,000 to $50,000 for a 30-day program.

Susan Romeo said it cost $40,000 for her son Joey to receive three weeks of treatment at Sierra Tucson, a rehab center known for treating several celebrities. He left the program before his 30-day treatment program ended.

Some inpatient treatment for opioid addicts can run as high as $80,000 per month, Geren said.

“I don’t think any kind of care matches $80,000 a month,” she said. “You’re talking about a year’s salary.”

Geren said she knows families who have spent between $50,000 and $100,000 – their life savings.

Outpatient treatment is available, usually at a much lesser cost. A year of outpatient methadone treatment, for example, costs about $4,700.

This type of treatment is also much cheaper than putting an addict in prison or jail. A year in jail can cost about five times more than a year of methadone treatment, according to the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

Romeo’s family pared back on their spending to pay for the care he needed.

“Everything I have is from the thrift shop,” Susan said.

She lives with her husband in a one-story house they bought as a foreclosure on the outskirts of Tucson. It has a pool in the backyard and mountain views.

“People look at our house, and go, ‘Oh wow, they must have money.’ Well, no, you don’t know my story,” Susan said. “You don’t know that when we had to coat the roof, I coated the roof. We didn’t call someone to coat the roof.”

Range of treatment options

The World Health Organization says detox alone – which basically means medical supervision while an addict goes through withdrawal – commonly leads to relapse and is rarely enough to help someone recover from opioid dependence. It recommends a diverse array of treatment options because no single form of treatment works for all people.

On one side of the spectrum, there are opioid treatment centers, which provide inpatient and outpatient treatment and incorporate methadone and/or buprenorphine.

These drugs imitate how opiates act within the brain, latching on to receptors that create a sense of euphoria. However, methadone and buprenorphine don’t fit into those receptors as well as opiates do – meaning that the right dose can eliminate withdrawal symptoms without causing the patient to feel high.

Still, these pharmaceuticals have appeared on the street and in prisons.

Nick Stavros, CEO of Scottsdale-based Community Medical Services, said their clinics take precautions to prevent methadone from becoming abused, including requiring patients to drink methadone in front of a nurse for a certain period of time before they can go home with doses.

At the Phoenix clinic, nurses keep bottles of methadone locked in a safe behind the counter. The clinic normally treats 300 to 400 people each day.

Some states have pushed back against expanded access to medication-assisted treatment. West Virginia, for example, has a moratorium on the opening of new opioid treatment centers in the state.

Stavros said banning medication-assisted treatment “is dissuading people from getting the one treatment that could save their lives. It’s totally terrible.”

Treatment facilities that dispense these medications must follow rigorous guidelines, including obtaining certification from the Drug Enforcement Administration and the federal government. Arizona has 36 such accredited opioid treatment programs, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Facilities that don’t provide these medications must still obtain a state license if they plan to provide medical care.

On the other side of the spectrum are sober living homes, which provide a post-detox, medication-free environment.

Arizona doesn’t track the number of sober living homes in the state, but some estimates reach as high as 10,000, according to a story by KPHO in Phoenix. Scottsdale officials believe more than 100 sober living homes operate within the city.

These homes take a 12-step approach.

In the 40,000-person city of Prescott, the sober living home industry exploded, causing resentment among local residents. Rep. Noel Campbell, R-Prescott, said he knew about 173 sober living homes operating without any regulations when he started working on legislation. He introduced a bill to raise the standard of care at these homes, and the governor signed the bill into law in May 2016.

“It was a horror story,” he said.

Lack of resources

Six years ago, Joanne Buchan, the mother of a recovering addict, said she couldn’t find a treatment center in Arizona that would accept her son’s Blue Cross Blue Shield insurance without a $5,000 copay. She said she managed to find one in California.

“We didn’t know where to turn or what to do,” she said. “There are people who say they will help you, but we found out they were like brokers. They would get commission for sending you to certain places.”

The Governor’s Office of Youth, Faith and Family has a treatment locator where users can filter facilities by location, type and forms of payment accepted.

“It’s a great first step,” said Samuel Burba, a program administrator with the office. “Finding and locating treatment – unfortunately – is a maze and people don’t know where to start.”

This locator is a great asset, Geren said, but is not comprehensive, and families still need to do their own research about the quality of care provided by each facility.

Researchers at Arizona State University also have pieced together a list of treatment programs.

The guide identifies nearly 100 opioid treatment programs in the state as of August 2015 and lists the type of treatment provided by each center (alcohol and/or opioid abuse) and the forms of payment each one accepts. Some do not take any form of insurance.

Adrienne Lindsey, a researcher at ASU who worked on the guide, said the team compiled information from state and national lists of providers and did their own research. Many providers don’t appear on any registries, so the team often found them by searching the internet.

Even when somebody does find a treatment center, they might not be able to get in right away. Those involved in the industry locally said addicts enrolled in the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, the state’s Medicaid program, often face waiting lists for treatment programs. Officials with AHCCCS have not provided a response.

Susan Romeo recommends that people carefully vet each center. Some can earn a reputation for having less-than-average, or even dangerous, standards of care.

“Every rehab center has a beautiful website. When you call them, they tell you exactly what you want to hear,” Romeo said. “Question everything, get things in writing. If you have a child in treatment, show up at that treatment center. Take a look at that treatment center. There are certain red flags. If you call and you’re not getting anyone on the phone, no good. Any reputable place is gonna have a full-time receptionist.”

Six years after he first got hooked, Joey Romeo now shares an apartment in a sober living home on the outskirts of Mesa with another recovering addict.

He moved in shortly after completing a 60-day inpatient program.

The sober living home, run by SOBA, costs about $150 per week. He said many of the staff are recovering addicts who have been clean for years.

Romeo said it would be easy for him to find drugs no matter where he is, even at the closest bus stop.

“I’ll be out there during the day, I’m gonna run into s—,” Romeo said. “That’s just how it works. I can get through that stuff and come back here and talk to someone. I have a place to come back to, a safe space.”

^__=