- Slug: Sports-AFL Day in Life, 1,827 words

- Photo available

By Madison Thacker

Cronkite News

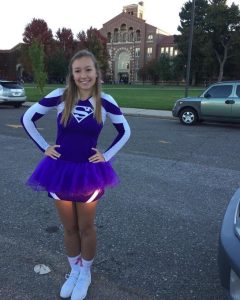

PHOENIX – It had been just like any other October day at cheer practice for Marlee Smith and her teammates at Denver South High School.

Then Smith’s day took an unexpected turn that would change her life and give her future a purpose.

Smith fell during practice, striking the side and the back of her head on the ground. The impact was so violent, it took 21 days before Smith regained her memory. She still doesn’t recall what happened that day in 2016.

Like so many other athletes, professional and amateur, Smith suffered a head injury. In the past decade, sports’ traumatic underbelly has been dissected from the halls of congress to the backrooms of high school coaches to medical boards at the finest hospitals. The subject of concussions – their cause and their treatments – sometimes takes precedence over the actual games.

When Miami Dolphins Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa suffered a head injury against the Buffalo Bills recently, the outcry led to new NFL concussion protocols that will likely trickle down to the youth level.

But few realize how common concussions are among cheerleaders. The sport is responsible for the third most catastrophic injuries (14.3%) among female high school athletes, according to data from the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research, behind soccer and track.

That number has improved recently thanks to more restrictions and improved coaching. Cheerleading was responsible for 65% of direct catastrophic injuries to female high school athletes during a 27-year period, according to a 2012 study by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Smith was already familiar with head injuries. She had suffered nine concussions, often referred to as mild traumatic brain injuries, before that fall.

Smith knew that this time, the injury was much more than that.

“I don’t know what exactly happened,” said Smith, 22. “From what we can see from how my injury was, I hit the side of my head, and so I had head trauma to my vestibular system. And then I fell back and hit my head on the floor.

“My mom told me that I at least got up and finished practice. So I have no idea if I took other hits to the head during that night. My coaches didn’t check me for a concussion at all.”

That was the end of cheerleading for the 16-year-old and a life-changing moment. The first week after the fall, Smith was removed from school and started treatment for a traumatic brain injury.

Rather than treat her as if she had suffered a typical sports-related concussion, her doctors began treating her as they would someone who survived a serious automobile collision.

It was the beginning of an unpredictable journey, but one that led to that purpose – advocating for those with brain injuries and educating others on the potential effects.

Early stages of recovery

Smith didn’t stop practicing that day, and it wasn’t until she got home that her mom realized something was seriously wrong with her.

“When she came home and said she crashed, and she’s like, ‘I don’t feel good. I hit my head.’ So I packaged her up and took her in (to the hospital),” said Susie Hagie, Smith’s mom. “And usually when it was something like that, she’s like, ‘No, no, I’m fine.’ And this time, she was just really docile and said, ‘Sure, whatever you want to do, mom,’ which is not Marlee.”

As soon as Smith entered concussion protocol, it was clear that her head injury was more serious and she wasn’t improving with rest alone. The fear started to grow for Hagie as she watched her daughter suffer.

Smith couldn’t stand up without nearly falling over, she couldn’t form sentences and had trouble remembering from day to day.

“It was really horrific. I was really afraid of how severe it was,” Hagie recalled. “At first, it was, ‘Oh, my goodness, is she going to be a functioning adult? Or do I have a really severe handicap now?’”

While these questions loomed over her mom, Smith was still unaware of what was happening as her brain was swelling.

To help reduce the swelling, Smith was prescribed Propranolol for a brief period. The drug is typically used to treat migraines but in some cases is used in traumatic brain injuries.

Robert Klingman, a physical therapist and clinical director for Movement for Life in Oro Valley, often sees patients like Smith who are struggling with multiple, prolonged concussion symptoms.

“Eighty percent of the people who experience concussion related symptoms typically will resolve in two weeks, so the people that we see in the office are usually the ones that are not getting better in those first two weeks,” Klingman said.

Smith’s dizziness, memory issues and balance are typical symptoms he and his clinic see when treating patients. Dizziness is often an indicator of a long recovery, Klingman said. He and his clinic evaluate a patient’s symptoms and put them on an individualized trajectory to help improve their symptoms.

“Not everybody has all of the symptoms that I just described,” he said. “Some people will have more of a dominant migraine type presentation where light and noise will affect their symptoms. Other patients will have more of a vestibular type concussion, which relates more to dizziness, balance related problems. Other people will have more cervicogenic symptoms, which means it’s coming more from their neck almost like a whiplash type mechanism.”

Klingman added, “We definitely work on these domains or these trajectories of a focus so that we do have an area and a system because typically with each of those trajectories, there’s going to be a specific treatment that is geared towards that.”

Smith’s trajectory included six to nine months of cranial sacral and chiropractic therapy twice a week. Smith still sees a chiropractor once a week to adjust her neck in an attempt to avoid migraines.

When school became a challenge for Smith, teachers and administrators struggled to understand why she suddenly needed special accommodations. Simple tasks like reading aloud became difficult. She had to relearn basic skills in therapy.

“I was doing everything there from relearning coordination and balance to working on puzzles and rebuilding neural pathways,” Smith said. “Speaking was hard. I stuttered a lot just because of the impact that I had and where I had brain damage.”

With Smith struggling with such basic skills, Hagie had to push for the school to provide the support needed for Smith to succeed again.

“With an invisible injury, she visibly looked fine,” Hagie said. “Teachers would ask her, ‘What’s wrong with you’? And there was a lot of me stepping in and saying ‘No, let me tell you what you’re going to do. Let me tell you what you’re not going to do. You’re not going to treat her like this. Here’s this documentation. Here’s this paperwork. Here’s what you’re going to do.’”

While dealing with a lack of understanding from teachers, Smith also struggled with her teammates. Her friends wondered when Smith would return to the squad.

She knew that would never happen.

“I don’t think you realize I’m not coming back,” Smith said. “You don’t get to come back from this. This is not how that works. At that point, 17-year-old me would have given my entire soul to cheer one more year. But it just was not going to happen. It wasn’t going to be my life.”

With the help of her mom, Smith got accommodations to finish high school. Smith’s course load included only necessary core classes.

It was always a goal of Smith’s to go to college and to pursue a degree in journalism. After her brain injury, Smith found a new love behind a camera, capturing images. So she decided she wanted to pursue a sports journalism degree and become a photographer.

To get into college, Smith needed to take the SAT test. One of the many difficulties Smith struggled with was memory recall, which is a necessity in most academic exams.

To her surprise, and that of her family, Smith was able to complete the exam and registered the fifth highest score in her high school class.

Smith and her family decided she would attend Arizona State University, the closest school to home that would provide her with opportunities to pursue her goals in photography.

Symptoms everlasting

At the end of her initial concussion recovery, Smith walked away with post concussion syndrome. According to the Mayo Clinic, post concussion syndrome occurs when concussion symptoms last beyond the expected recovery. The usual recovery period is vague and can vary from weeks to months.

Smith continues to experience some symptoms now, more than six years after the accident. Persistent migraines cause her right eye to go numb and affect her vision. It affects her day-to-day, including her ability to take photographs. Smith communicates with her co-workers and is always prepared for a migraine to strike.

“There are parts of my brain that will just never develop the way that they’re supposed to,” Smith said. “And I still have things like chronic migraines. I still have neurological symptoms if I get a certain level of stress or overwhelmed.”

Completing her degree was an uphill battle for Smith. She struggled to have professors understand her needs and struggled to complete the language requirements for her degree.

With the parts of her brain that understand language being affected, understanding a new language was a difficult task for Smith.

“I took Spanish 14 times,” Smith said. “It was so frustrating because not everybody, especially in my case where part of the injury that I had was with language and the language processing center of your brain; it was so frustrating all of college because it does make you feel like you are a failure.”

But Smith persevered and finished her language requirement to graduate with a degree in sports journalism in May of 22. She now works for AT&T, running social media accounts and serves as social director for Miss Rodeo Arizona. One of Smith’s many passions is covering rodeo events as a photographer.

Despite these successes, everyday working life still comes with struggles for Smith. Some days, she needs to take long breaks to nurse a migraine.

Smith’s biggest advocates

From the beginning of her injury, Hagie has advocated for Smith and has helped her navigate this new normal. Now living out on her own, away from her mom, Smith leans on her boyfriend, Robbie Malles, to step in and help in the moments when she can’t advocate for herself.

Just over a year ago, Smith met Malles, a former professional bull rider, at an event she was covering. Shortly after meeting Smith, Malles learned about Smith’s traumatic brain injury. He now helps Smith recognize the triggers for her migraines and helps to remove her from those situations.

“The biggest thing that I could do for her is constantly reassure her that her health is far more important than a concert or watching fireworks or anything of that sort,” Malles said. “Her health and well being is always going to trump everything else.”

As a former bull rider, Malles is no stranger to concussions. He stepped away from the sport in July and now recognizes symptoms of the concussions he received while competing. When Malles was 10, his dad also suffered a traumatic brain injury, giving Malles a unique understanding of what Smith is going through.

And Smith understands Malles’ struggles as well.

“I’m finding myself slipping, I’m finding myself starting to deteriorate, it seems like some days, I can’t put together basic sentences,” Malles said. “Some days, I can’t remember what I had for dinner last night. In the sense that I support her on a regular basis, because she has been through one, she supports me on a daily basis, also.”

Malles and Smith recently lost a friend, who was a bull rider, to suicide and after his passing he was diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. According to Mayo Clinic, CTE is a term used to describe brain degeneration and is likely caused by repeated head trauma. It is a condition that has led to dramatic rule changes and new head injury protocols in football and other sports.

Malles’ perspective on his sport changed and made it an easy decision for him to hang up his chaps and bull rope for good.

“It definitely helps support the decision to retire and to be done with it,” Malles said. “Because I already went through enough with what I’ve been through. I didn’t want to make it worse because head injuries cause you to change. It changes your actions and things you can do. It’s not necessarily what you want.

“Do you want to go on a roller coaster? Of course. Are you sensitive to quick motions? Yes, so you can’t. It sucks.”

With Hagie and now Malles, Smith surrounds herself with people who understand what she needs and are willing to fight to protect her health when she can’t do so herself.

Hope for change

Smith’s experience has opened her eyes to a lack of awareness around concussions and traumatic brain injury in sports and led her to advocate for awareness.

The subject is again in the national spotlight following Tagovailoa’s two concussions, which forced a change in NFL protocol.

Despite the changes in protocol, NFL players suffer concussions weekly. In week seven, four players were ruled out for concussions. With more concussions happening more now than ever, Smith sees the need to advocate for the ‘invisible injury’.

“One of the biggest things that I feel like it’s really important to talk about that isn’t talked about enough is something called the ‘invisible injury,’” Smith said. “When you break your arm, people can see that you’re in a cast. People can see that something happened, and you can’t see a concussion.”

Smith tells her story through her social media platforms and has teamed up with the Brain Injury Alliance of America to create an influencer campaign to share her experiences.

Hagie and Malles stand by Smith’s efforts to make concussions and head injuries “seen.”

“She turned a lot of those really negative things into positive parts of her life,” Hagie said. “And I love that she’s a fierce advocate for TBIs.”

Malles agreed and added that education is a big part of the effort.

“Concussions are something that we just don’t talk about a lot,” he said. “You can’t see what someone is truly dealing with in their brain, having gone through multiple injuries or even one significant injury. I think it’s something we just need to normalize the conversation and advocate for someone to take more time to let their brain heal.”

Smith hopes for change and that others will recognize that one size does not fit all when it comes to head injuries.

“You may not be able to see it, but I’m struggling inside,” she said. “But the person sitting next to me, who also has a concussion, is struggling in a very different way than I am.

“There are so many parts of your brain that do so many different things, that damage to those parts drastically change what your healing process looks like, what your rehab process looks like, how you need to do things differently in your day to day life.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.