- Slug: Sports-Youth Analytics,1880

- 3 photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

By Tyler Dunn

Cronkite News

PEORIA – With the game tied 9-9 in the bottom of the sixth inning, Mathew Swedler smashed a line drive to center field, scoring Kyler Thruston for the go-ahead run.

Swedler, 13, advanced to second with a five-pitch walk to teammate Jackson Forbes and made his way to third after an error by the opposing shortstop. One pitch later, he scored easily on a single to left field.

Just inside the dugout of AZBC 2024, a Peoria-based 13-and-under club team, assistant coach Kevin Forbes sat hunched over an iPad, inputting each step of Swedler’s trip around the bases.

In many ways, youth baseball resembles the game of Forbes’ childhood: Saturdays spent at the ballpark, a dust-coated mixture of eye black, chatter and competitive tension swirling in the air. But that iPad, and the wealth of data stored in it, represents a revolution within a sport long resistant to change.

Analytics have been a part of baseball for decades but are most often discussed in the context of Major League Baseball. What’s less considered is how that movement has trickled down into the lowest levels of the sport and how it has changed the way children learn to play it.

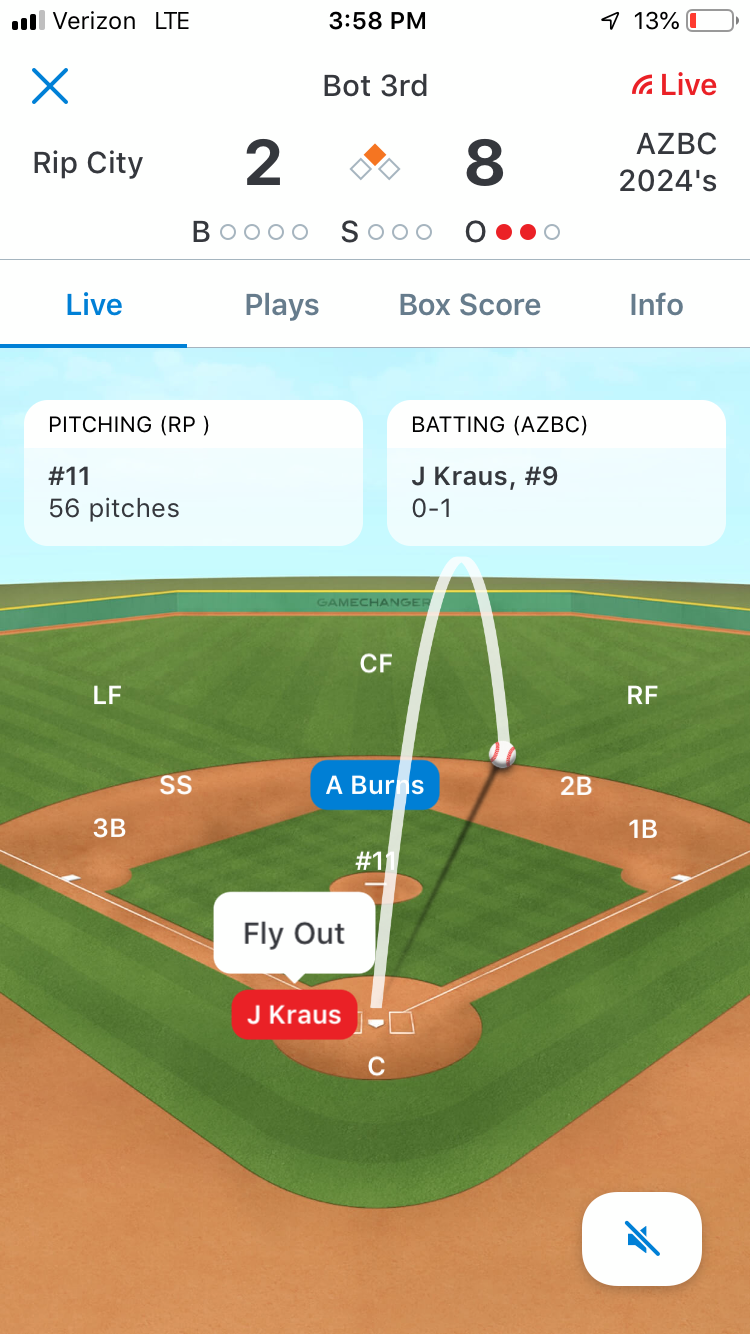

One way it has: a scorekeeping app that updates in real time and, along with the same basic stats recorded in a traditional scorecard, has more than 150 advanced metrics.

Jimmy Sanderson, an assistant professor at Texas Tech’s Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, started studying the impact of that app, GameChanger, after parents on his son’s Little League team began using it.

“The professionalization of data has become common-place in Major League Baseball,” Sanderson co-wrote in a 2018 academic paper, “and now through GameChanger, it also enters the youth game.”

Pork-and-beans beginnings

As with most earthquakes, the movement started small.

Water sloshing toward the rim of a cup, a bookshelf animating with the slightest of rattles – that was baseball in the late 1970s, when a then-unknown Bill James first applied statistical analysis to better understand the game he was seeing. He later called this study “sabermetrics,” a nod to the Society for American Baseball Research, based in Phoenix.

James, a native Kansan, spent his nights as a security guard for a pork-and-beans cannery trying to crack the game of baseball, poring over simple box scores, positing, extrapolating. He self-published his efforts in 1977, the first of his legendary “Bill James Baseball Abstracts,” and advertised it in the baseball-oriented magazine The Sporting News. He reportedly sold 75 copies.

With each issue of “Baseball Abstracts” came true innovations, like Runs Created, a formula intended to gauge offensive production through a combination of a player’s on-base totals and extra base hits. James tinkered with the formula for decades, but at its most basic form, it looked like this:

TB x (H + BB) / (AB + BB)

It was that kind of thinking that would lead future sabermetricians to call him the father of a movement. On his shoulders, metrics like exit velocity, launch angle, xwOBA and DRC+ would quantify baseball in ways not even James could have imagined. And yet, as the 1970s gave way to a new decade, his readership remained small.

“What is remarkable to me is that I have so little company,” he wrote in his third “Baseball Abstracts” installment. “Baseball keeps copious records, and people talk about them and argue about them and think about them a great deal. Why doesn’t anybody use them?”

Eventually, the right people started paying attention. Billy Beane, who became general manager of the perennially purse-strapped Oakland Athletics in 1997, was an early James disciple. He was a first-round pick in 1980 and, at 6-foot-4 and 195 pounds, looked the part, the kind of player who inspires folklore in small-town coffee shops across America. But he flamed out after six big league seasons, ending with a career three home runs and a .246 on-base percentage.

Guided by his own experiences and James’ writings, Beane had largely thrown out conventional wisdom by the early 2000s and started seeking out players who were his exact opposite. Fat, plodding, defensively challenged – none of it mattered, as long as a guy could score runs.

Beane’s story is the focus of Michael Lewis’ “Moneyball,” released in 2003 following Oakland’s improbable 103-win season. It quickly hit bestseller lists and sold more than one million copies before its theatrical adaptation in 2011, according to the Wall Street Journal.

James, Beane and Lewis weren’t the only people responsible for introducing data into baseball. Henry Chadwick, Allan Roth and dozens more made sports-altering contributions in that area. But it was James, Beane and Lewis— along with Brad Pitt—who brought analytics into the mainstream, the ones who brought us here.

‘A raw skills guy’

Before Forbes coached baseball, he played it. The California native was drafted by the Montreal Expos in 1996 after one season at American River College in Sacramento.

But he struggled to adjust to professional baseball.

“You go from signing where you’re a junior college All-American and league MVP and all of these things, and then you get to professional baseball and everybody’s an All-American and everybody’s an MVP,” Forbes said, recalling the competitive atmosphere he encountered on his first days in the minor leagues. “You’re in a locker room full of guys who were all that and more in their respective areas. So, it’s a wake-up call.”

Much like Beane, Forbes was a naturally gifted athlete and, by his own admission, more of a “raw skills guy” than a student of the game. He needed coaching, but said when he looked for instruction during that pivotal entry into professional baseball, he was turned away. Expos policy at the time, according to Forbes, was that new players would perform on their own for 30 days before coaches stepped in.

“It was all, ‘We’re just gonna watch. We’re gonna see what you are, what adjustments you make on your own and after that, we’ll have discussions,’ ” Forbes said. “And if you’re struggling, that’s frustrating.”

He scuffled through two seasons in the low minors before surprising management with a request for his exit physical. He was done – and he was exasperated. Forbes returned to independent league baseball after a four-year hiatus, but his time in the Expos organization would be his first and last in an MLB system.

Forbes was 28 when he retired fully from baseball in 2004, a year after the release of “Moneyball” and the wave of data it ushered in.

But embracing data “was streaky. It was all feel for me,” Forbes said. “Not because I was anti-information, I just didn’t have it. It wasn’t being provided at the time.”

He opted for a different life, one with a wife, two sons, a stable job outside of Phoenix. And one, he said, far away from baseball.

“For a while, I was just bitter. I missed the game so much. I couldn’t,” Forbes said, pausing. “I couldn’t go to games anymore.”

Years went by before he was able to take his boys to a game. When he did, he saw the sport with fresh eyes.

“It’s no longer, you know, the business, the missed opportunity,” Forbes said. “It’s, ‘My kids love this.’ And so they started playing baseball.”

For a while, Forbes tried to stay away from coaching as he questioned whether he would be able to teach pre-teens after reaching such a competitive tier of the game. But once the other parents learned they had a former pro player in their midst, he dusted off his cleats and returned to the dugout.

Digging into the data

Around the time Sanderson discovered GameChanger, Forbes and his fellow coaches did, too.

Now, a hit past the shortstop is no longer just scored as a single on, say, a 2-2 count. It’s a line-drive single pulled to left field, connected with after taking a first-pitch strike. Zoom out, though, and that single can be mapped into a spray chart showing where a player hits the ball. That one play will factor into the player’s line-drive percentage, quality at-bat percentage, total bases, at-bats per home run and dozens of other data points.

Kresta Davis, who scorekeeps through GameChanger for a Little League team Forbes also coaches, said she quickly found the value of the app after taking on scorekeeping responsibilities two seasons ago.

“For Kevin and for my husband, who love the numbers of the game and want to make sure that everybody’s getting credit for what they’re doing on the field, this app is fantastic because it just keeps track of it all,” Davis said.

Forbes recognizes the pitfalls this kind of information can bring: an over-analytical approach and an undervaluing of fundamentals – or in his words, making “kids into stat-rats.” He’s careful with how much he shows his players who, regardless of talent, are still kids. But based on the lessons he learned during his own baseball career, he tends to think “more information is usually a better thing.”

In early January, Forbes decided to share some of what GameChanger had gathered with his oldest son Jackson. With more than three months of data to pull from, Forbes showed Jackson that he had more strikeouts than any pitcher on AZBC. He also showed him that he led the team in walks.

“You don’t have to be perfect,” Forbes told his son. “Your stuff is good enough. You have to have some trust in your stuff and stop trying to strike everybody out.”

Since then, Forbes said Jackson takes the mound with more confidence and better results.

“The mindset is different,” Forbes said. “He walks out there now like, ‘Here it comes.’”

Applying the data

Thousands of high schools and youth baseball teams across the country use GameChanger, too. Dick’s Sporting Goods bought the app in 2016 and has partnered with Little League and the National Federation of State and High School Associations in recent years. GameChanger is even a partner of MaxPreps, a high school sports and collegiate recruiting website, and is able to quickly automate stats onto a school’s page.

GameChanger is far from the only emergent technology to have found its way into youth baseball. The company Blast Motion markets a motion sensor able to attach to a player’s bat and record hyper-specific elements of a swing, like peak hand speed and “attack angle.” Motus Global developed a compression sleeve that measures a pitcher’s workload.

But as much as these products are changing every level of baseball, it’s the depth to which data has embedded into people’s thinking about the sport that has been the most transformative.

“Our head coach on our club team talks about us being at 70 percent first-pitch strikes,” Forbes said. “We’re trying to get ahead early, minimize the number of pitches, walks, all that kind of stuff.”

We can’t know how Forbes – or Beane, for that matter – would have performed if they’d had access to the amount of data available to today’s players, or the analytically supported lessons pre-teens are absorbing without even realizing it.

And they can’t either. But they can pass on what they learned to the next generation of players.

“We can teach you how to field a ground ball and be on the mound and all of the physical stuff,” Forbes said. “It’s the mental piece that separates you.”

Follow us on Twitter.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=

Former professional baseball player Kevin Forbes just missed the sport’s data revolution. He’s making sure his two boys don’t miss it, too. (Photo by Tyler Dunn/Cronkite News)

In his first full season as an assistant coach with AZBC 2024, Kevin Forbes has used GameChanger to analyze his players’ performances more than ever. (Photo by Tyler Dunn/Cronkite News)

In addition to storing a wealth of statistics, GameChanger allows for people to keep tabs on the game from anywhere in the world. (Photo by Tyler Dunn/Cronkite News)