- Slug: Sports-Tennis Globalization, 3,000 words

- Photo available

By KAELEN JONES

Cronkite News

TEMPE — More than a decade ago, Arizona State men’s tennis coach Matt Hill was hoisted 30,000 feet in the air, fixed to the seat of a plane flying from Germany to the United States.

Christmas break was intended to be a period of repose for Hill, then an assistant with Mississippi State men’s tennis team. Instead, he found himself embarking on a recruiting trip to Germany, where he spent two days pitching his program to a prospective player.

Upon returning, Hill took a moment to himself, when a realization struck him.

“Wow,” he said to himself. “I just flew halfway around the globe to spend two days with a kid.”

Hill, who has coached in various capacities for 13 seasons in Division I tennis with three different teams, has made several journeys since then. Not all have been successful.

“He came,” Hill said. “So it was worth it.”

Finding worth in the trek would become essential to sustaining his career.

The international footprint

During the past two decades, collegiate tennis has seen a dramatic increase of international influence.

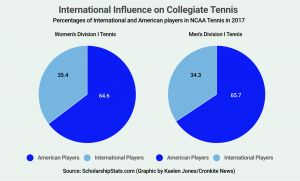

In 2005, 28.4 percent of men’s college tennis teams and 21.5 percent of women’s college tennis teams were comprised of foreign players, according to the United States Tennis Association (UTSA) and Intercollegiate Tennis Association (ITA).

Per ScholarshipStats.com, those figures jumped to 32.3 percent in men’s tennis and 30.4 percent in women’s by the 2013-14 season. Last season, international players made up 34.3 of men’s college rosters and 35.4 percent of women’s.

The 2017-18 ASU tennis program — both men’s and women’s rosters — shattered those percentages, fielding a combined 13 of 17 total players (76.5 percent) from foreign lands. Eight of nine men’s players hailed from other countries. Six of eight players were foreign on the women’s team.

For the men’s side, the arrangement is understandable.

The Sun Devils men’s tennis program was reinstated in May 2016, earning varsity status after being discontinued at ASU in 2008 due to budget cuts. Hill was charged with the unique task of building a roster from the ground up, selling the idea of being the foundation of a program.

Feasibly developing a roster hinged on his ability to recruit internationally.

“Huge,” Hill said of the help a worldwide pool offered his efforts to enlist players. “We wouldn’t have been able to do what we’re doing now.”

Furthermore, access to the international talent affords coaches the ability to recruit the best possible players to their schools, an imperative factor in order for staffs to maintain their jobs.

Many have suggested the exponential increase of international players is an indication of tennis’ progressiveness. However, throughout the years, pushback and concern regarding the inclusion of foreigners in collegiate tennis has countered the notion.

Per ScholarshipStats.com, there were 191,000 high school tennis players in the United States, but only 2,417 collegiate tennis scholarships available. Home-grown players have to compete for collegiate spots not only with their American peers but with those across the world who may consider playing collegiate tennis.

Opponents to the approach argue that taxpayer dollars shouldn’t be spent to aid foreigners and that American-born players should be more widely considered for scholarships — even though statistics show they still account for the majority.

In 2005, the UTSA, in tandem with the ITA, issued a seven-page document addressing the influx of international players in American collegiate tennis. The topic was described then as a subject “that has involved more controversy, emotion and misunderstandings over the past two decades.”

In an attempt to ease worry, the document pointed to increased globalization and tennis’ universal growth, noting that “the college landscape is a reflection of what is occurring on the world stage.”

The sentiment is accurate based on the makeup of the professional tennis field. The United States presently accounts for just 23 of the 200 top-ranked tennis players in the world between both the men and women circuits.

Nine American men are rated in the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) top 100, including three in the top 20 (John Isner, ninth; Sam Querrey, 14th; Jack Sock, 17th). The next highest-ranked American is Tennys Sandgren, a former University of Tennessee player, who’s ranked 47th.

There are 14 American women placed in the top 100 of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) rankings, with four in the top 20 (Venus Williams, eighth; Sloane Stephens, ninth; Madison Keys, 13th; Coco Vandeweghe, 14th). The next highest-ranked player is Catherine Bellis, who’s No. 44 in the world. (Serena Williams, winner of 23 career Grand Slam tournament titles, wasn’t included in the top 400 of the world.)

Considering the obvious international footprint in tennis, Hill asserts that the collegiate game is beneficial to American players, giving them a taste of what the professional tour would present them.

“I think it strengthens American tennis,” Hill said. “The really good Americans that are going to the elite schools are getting exposure to the best players around the world as well. That only helps our American players prepare for the tour, because if they’re going to go out there and try to compete at the U.S. Open and Wimbledon, they’re going to need to see different game styles — which you get a lot of when you’re playing players from different parts of the world.”

The recruiting process

Hill spent a significant amount of time overseas recruiting players to join ASU’s squad. This was partially due to so few American recruits left to choose from by the time the Sun Devils staff got started on the recruiting front.

The recruiting process for American tennis players begins much earlier than it does for their international counterparts, with players typically deciding where they want to play by their junior year of high school. Foreign players, on the other hand, don’t usually consider coming stateside until their senior year or even later.

This is why Hill thinks the globalization of tennis and the NCAA’s openness for international recruiting is an advantage tennis has in comparison to other sports that would be restricted to domestic recruiting.

“We wouldn’t have been able to field a team, a team that could be competitive in the Pac-12, if we were a sport where we are only (recruiting American players),” Hill said. “Because there are sports that we are supporting here that they don’t play them internationally, so they’re kind of handcuffed in a sense that if their recruiting cycles are early and no one plays the sport outside of the U.S., then yeah, you’re in a pickle.”

Hill’s conviction also backs the opinion that the international pool enables teams to field the best possible roster. He acknowledged the counterpoints against global recruiting, but added, “at the end of the day, our jobs are on the line to be competitive with each other. So we have to, just like a Fortune 500 company will do, they’re going to hire the best employee, and we’re going to do the same.”

Like any company, cause for people to join a campaign must be enticing. Hill had to sell a program that didn’t yet exist, which for a few players, was admittedly nerve-wracking. Some found the idea exhilarating while others were cautious.

Connections Hill and his coaching staff had both previously established and proactively forged aided in the effort to form the Sun Devils’ current roster. ASU’s men’s tennis team is composed of eight international players — the most any Pac-12 roster boasted this past season. Seven of the players hail from European countries, giving the squad a markedly European charisma.

Freshman Thomas Wright, who hails from Beckenham, Great Britain, had kept in contact with Hill after he gauged Wright’s interest in playing for him at the University of South Florida during the summer of 2016. They maintained proper contact, and when Hill left USF for ASU, Wright followed.

Wright explained that it’s normal for college coaches to come and visit in-person when permitted to do so in accordance with NCAA rules, but initially there’s plenty of dialogue over the phone. Restrictions for contact with recruits lighten as players progress through their high school careers.

“When they do come over,” Wright said, “you sit down and have a dinner or a lunch or wherever you decide to do it, and they talk to you more. They kind of really try to encourage you to try and get out of there.”

The opportunity to play collegiate tennis in the United States was a chance that hasn’t come without personal and external scrutiny for foreign players. For example, Wright entertained the idea of playing in the United States as a teenager.

When Hill tried to convince Wright to play at USF, his mother, Sam, told him he was too young at the time.

“I was maybe a little too young to come out,” Wright said. “But definitely, my mum kind of knew I always wanted to come out here from an early age. So it was just a matter of time before I got on that flight and I came out here.”

Considering the talent present outside of the States, it begs one to wonder why a foreign player would choose to play collegiately, particularly in America. Several players offered different reasons.

“The university side here is so much better than back home,” Wright said. “You get your degree and the tennis level is really high — that’s the important thing. You don’t get this really anywhere else in the world. This is the best place to come.”

Freshman William Kirkman, originally from Cabarete, Dominican Republic, said that the idea of playing collegiate tennis is considered a controversial issue outside of the United States.

“A lot of people who don’t live in the U.S., they think about college, and college is like an ending point for your career,” Kirkman said. “Kind of last chapter to get your degree and then you’ll quit sports because you’re going to pursue a job. Whereas I think college tennis has really turned into, if anything, a really big starting point at any chapter where you can have all these opportunities — three coaches on court, great facilities, awesome equipment — to begin your professional career.”

Michaël Geerts, the Sun Devils’ captain and No. 1 singles player, understands exactly what Kirkman is referring to when alluding to the idea that college tennis is perceived as a closing point in one’s tennis career.

The Belgian senior was one of the most talented players in his homeland, and played for the Belgian Tennis Federation for his entire life. He played on the professional circuit and achieved a global ranking as high as No. 435.

At 18 years old, Geerts doubted whether he wanted to come to the United States to play because the Belgian Federation wanted him to remain at home. He decided to stay, then two years later finally moved on to America.

“I have to admit, I think in Europe, college tennis is underrated,” Geerts said. “Most of the coaches don’t have an idea, I think, about how high the level actually is and how important college tennis is and how important college tennis is or how well or how good the facilities are here.”

Moreover, international players are encouraged by what previous foreigners were able to accomplish in their professional careers after playing collegiately in the United States.

“You see some of the top players (from the) Juniors (level) coming here,” Wright said. “Like Axel Geller, he was the No. 1 in the world Juniors. He went to Stanford.”

Added Kirkman, “That’s how it’s kind of shifting for me. In the last 10 to 20 years maybe, there’s many examples of kids on the tour. Like Steve Johnson, he played at USC. Mackenzie McDonald, he played at UCLA. So those guys are inspiring for us.”

Taking advantage of the opportunity

Since arriving to ASU, Geerts has accomplished a rare feat, defeating the two top-ranked players in the country. Earlier in the season, he topped No. 2-ranked Mikael Torpegaard of Ohio State during a match at Indian Wells, then last week beat No.1-rated Martin Redlicki of UCLA inside Whiteman Tennis Center.

The victories felt noticeably different from what he was used to experiencing at home in Belgium.

“Where I was in the Federation — sometimes, I had the feeling it was black or white,” Geerts said. “Here in the States, I have the feeling that everything is a little bit more positive, I would say.”

As Geerts wrapped up his latest victory and the Tempe crowd roared, it finally hit him.

“That was kind of like, ‘Oh, wow. It really does mean a lot here,’ ” Geerts said. “Being in college tennis and everything, it’s really fun to see how involved the people are here and the tennis and the results. Although you’re not maybe doing that well, they really motivate you to do better and play well in the future.”

The collegiate tennis culture is a complete 180-degree turn from what ASU’s international members are accustomed to, and this is an adjustment they’re required to make simultaneously to adapting to a foreign society.

“The first month or so of being in America was very different,” Wright said. “Everything’s bigger here, everything’s bolder. So it took some time to get used to, but I settled in and had these boys to help me out as well. We all have each other which is pretty cool.”

Coursing the path towards professional status requires players overseas to advance through the Juniors level, competing in tournaments all across their home continents and sometimes beyond. The training sessions and matches are individualized and even the trips along the way can be lonely.

The collegiate tennis setting in America breaks from that individualization almost entirely. The consensus suggests the greatest difference is the fact the game isn’t so personalized.

“It’s much different,” Wright said. “The drive here behind the coaching, everything’s much more different. Everyone’s much more encouraging. There’s a big team feel when you come to America. Back in Europe, it’s very individual. You kind of do your own things, whereas you come out here and there’s eight guys all driving for the same thing.”

Kirkman said it’s much more motivating to play in the collegiate tennis environment where one is surrounded by teammates and coaches. He recalled a time when he travelled to Honduras, visiting two cities for a tournament via bus by himself through what he described as rougher areas.

He performed well, winning the tournament he competed in, but can still remember the uneasiness of being alone.

“You have coaches, but they’re not allowed to be on the court,” Kirkman said. “No one’s allowed to be with you on the court but yourself. So you feel lonely. Sometimes you travel alone. Sometimes you even travel without a coach to save expenses.”

Now, the trips are much more enjoyable. Kirkman lauded the beauty of campuses of Pac-12 schools he’s visited, joking that travelling in the United States isn’t very difficult because his flights are rarely delayed.

“So it’s like you’re enjoying every step of the way — the hotels, being with the teammates and the really nice campuses.

Of course, the scene is more relaxed and team-oriented at the collegiate level, which is helpful. But the camaraderie between the players has certainly helped in their transition to the United States. In fact, their chemistry is eminently noticeable; the Sun Devils’ men’s tennis team boasts a European charisma whose collection of personalities are just versatile and dissimilar enough to fit cohesively.

This isn’t necessarily unfamiliar territory for Hill, a 13-year coaching veteran who’s welcomed the increase of international competitors.

“It’s been a lot of great international players,” Hill said. “But some of my colleagues that have been here a little longer said yeah, probably 20 to 25 years ago, it wasn’t as much it is now. But that’s just the sport. When you look at the sport over the last 30 years, even from a professional level, has gone way more global than it was. So you have tons of sports (or youngsters) that are playing tennis now and supporting tennis that 20 or 30 years ago wouldn’t have even picked up a racket.”

With more and more players finding their way to the United States to play, Wright said he thinks it’s becoming common that foreigners are urged to play college tennis. The stigma it once held in the eyes of those overseas is beginning to vanish.

“Nowadays, players are starting to get pushed more to come out here,” Wright said. “Before, definitely not. It was all about trying to turn pro straightaway and coming here it was almost like failing. But now, it’s the complete opposite. People will encourage us to come out here. It’s a very important aspect because yeah, as a junior, when you’re travelling, you’re travelling at 14, 15 years old, just you and your coach, or you and your mum or dad. That’s not really how it is now, where you get on a flight with eight other boys, you go to the same location, you stay with each other at a hotel, have some fun. So it’s a big, big difference.”

While many will contend that offering scholarships to those from other countries shouldn’t be celebrated, the players arriving are assuredly working to take advantage of their opportunity, as well as expressing gratitude.

“Everyone sees the importance behind college tennis,” Wright said. “And it’s a good stepping stone to go to the pros.”

Statistics suggest that the international mark on collegiate tennis will likely only continue to grow. The development is something Hill deems as a positive on the game not only domestically, but for the sport’s competitiveness universally.

It will likely mean more trips like the one he ventured on years ago, but just like it was then, the reward is perhaps worth the investment.

“Tennis is such a global sport,” Hill said. “There’s such great tennis all around the world that it doesn’t — whichever way you go, you can get some great players and really compete at the highest level that tennis has to offer.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.