- Slug: Sports-Kush legacy, approximately 800 words

- Photos available

By SETH ASKELSON

Cronkite News

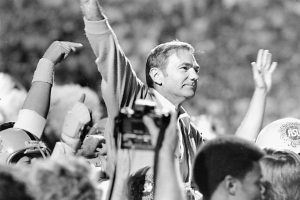

PHOENIX — Frank Kush was defined by his accomplishments and controversies but his impact on the growth of Arizona State as a university should be his greatest legacy.

That’s the belief of many about ASU’s winningest coach, who passed away early Thursday. He was 88.

“He put ASU on the map long before it was a full-scale university,” university President Michael Crow said in a statement. “By growing ASU football, he helped us build the whole university into what it is today.”

When Kush took over the program in 1958, then-Arizona State College was fighting for the passage of Proposition 200, which would turn the school into a full-fledged university. The young coach crisscrossed the state to help promote the move.

It passed. Kush’s contributions to the growth of the university continued by doing what he did best: winning.

He was the football coach until his dismissal in 1979. He posted a school-record 176 victories, but his 16-5 record against rival Arizona is one of his most celebrated feats.

Kush logged 19 winning seasons, including nine conference championships. He had unbeaten streaks of 21, 13, and, on two separate occasions, 12.

“I don’t care if you’re talking Barry Goldwater or Carl Hayden, I don’t know anybody else that would’ve made a bigger impact on the state at the time,” said Steve Matlock, an offensive lineman who played under Kush from 1969-1973.

ASU Vice President of Athletics Ray Anderson said, “When you think of Sun Devil football, you think of Frank Kush.”

Kush was relieved of his coaching duties in 1979 after allegations he tampered with an investigation into charges that he punched punter Kevin Rutledge. He was acquitted two years later in a related lawsuit.

His legacy with the university is complicated. Despite how his career ended, a bronze statue of the coach sits outside Sun Devil Stadium, where a field is named after him. He is revered by many.

“He loved the media and I think everyone that covered ASU football during his tenure … loved him because he told it like it was,” said Suns play-by-play voice Al McCoy, who was a broadcaster for ASU football on the radio during Kush’s first season at the school.

Kush had 128 players drafted by professional football leagues. Among those is J.D. Hill, who was drafted by the Buffalo Bills fourth overall in the 1971 NFL Draft. Much of what Kush taught him helped him prepare for the NFL, Hill said.

“The toughness, the practices,” Hill said. “We would practice two or three times a day (at Camp Tontozona). When we came down into the Valley, we were ready to play.”

Kush accomplished almost as much off the field as he did on it. Not only did he help the school become a university, but his success helped the creation of Sun Devil Stadium and the Fiesta Bowl.

And he had a presence about him.

“He was one of those people who could walk unannounced into a room and you’d get this feeling and look around for a bit,” said former Arizona Republic sports columnist Tim Tyers. “And then you’d see him there and say ‘I knew Frank was here.’ ”

Kush stayed involved in ASU athletics long after he finished coaching. He had great success in one sport but happily dabbled in others.

“We had a basketball clinic one summer and invited coach to come over and sit in and he did,” said former ASU basketball coach Herb Sendek, now at Santa Clara. “Even though at that time he was retired from coaching, he was still taking notes and participating.”

Kush’s no-nonsense attitude stretched beyond players and media. Many in the community were able to experience his personality.

“He knew everybody, and everybody knew him,” Matlock said. “And they all knew he wasn’t a very flowery ‘hey, let’s go have a beer’ nice guy. He was ‘we’re on a mission and we’d like your support.’

“Whether it be a booster or a player, it didn’t make any difference … ‘Are you in or are you out?’ ”

While all the numbers and records will be around long after his passing, his legacy will not be solely defined by football.

“The players becoming men and making positive impacts everywhere they went,” Matlock said. “When we got finished (playing), you knew that whatever you set out to do, that you were going to do it in a fashion that would give you a step up on the other guy. That you were going to work at it because we worked harder than anyone who played the game.

“You weren’t going to be the best at it. But you were totally fearless.”