- Slug: BC-CNS-Refugee Students,1080

- Photo, video story available (thumbnail, caption below)

By ALEJANDRO BARAHONA

Cronkite News

PHOENIX- Jolie Zuza came to Arizona as a child in 2005, fleeing war and death.

The turmoil in East Africa destroyed her family. She says her father died of sadness after watching the murder of her sister and nearly losing her older brother at a refugee camp in Burundi.

The series of tragedies qualified Zuza’s family for political asylum in the U.S. and help from an aid program for refugees, the International Rescue Committee.

The program helped her mother find a job and a furnished apartment in Phoenix. Zuza, now 19, was 9 at the time and did not speak a word of English when she was enrolled in the fourth grade at Balsz Elementary School in Phoenix.

“I was scared,” Zuza recalled. “Going to school with people when you don’t even understand the language. I was feeling like they’re going to look at me like, ‘She’s different.’”

Sometimes, Zuza snuck out of class and ran home out of fear and frustration. She speaks seven languages, including Swahili, Kirundi and Kinyarwanda, but learning English was a challenge.

Other immigrant children attended her school and did not speak English. But those who had been in the U.S. longer helped the newly arrived students by translating the little English they knew, Zuza said.

Schools in Arizona have long offered immigrant students English learning programs such as English as a Second Language, known as ESL, and, most recently, English Language Learner, called ELL. But those programs were initially tailored for Spanish speakers. Many Arizona immigrant students come from Spanish-speaking countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and others in Latin America.

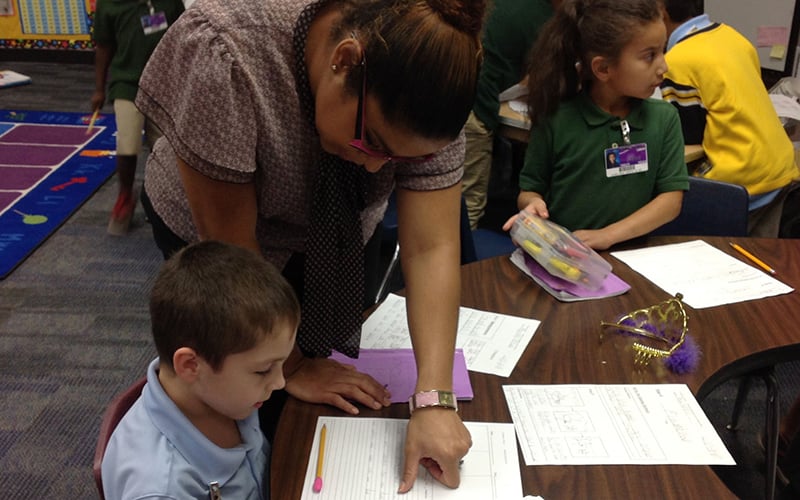

Teachers have to use other methods to help students who don’t speak Spanish. Angelica Martines, a first-grade teacher at Porfirio H. Gonzalez Elementary School in Tolleson, specializes in teaching ELL students.

“The most difficult part is communication,” Martines said. “I feel like, intellectually they’re really smart, they’re capable of doing the work.”

Martines uses pictures and models to effectively teach words and sentence structure. She also uses computer-software programs such as Rosetta Stone for those who speak less-common languages.

“We never had a translator at our school,” Zuza said. “We just go and then the teacher puts you in front of a computer.”

In her 12 years of teaching, Martines has mostly worked with Spanish speakers, but now she teaches African and Filipino students as well.

‘100 different languages

Teachers like Martines will be in demand.

More than 4,000 refugees came to Arizona in 2015, according to the Refugee Resettlement Program coordinated by the Arizona Department of Economic Security. The number was expected to increase in 2016.

That is putting a strain on public schools, where the struggles of teaching and learning are weighted with hundreds of students who need to learn English, not only to succeed at school, but navigate a new country.

Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Diane Douglas said many districts in the state serve students from all over the world.

“When I was on the Peoria school board, I think they told us at one point we provided services to students with over 100 different languages. That’s a huge burden,” Douglas said.

An Arizona Department of Education spokeswoman said Arizona’s program for English learners is “inclusive.” Programs are meant to help students learn English as quickly as possible, or within the year suggested under Arizona law.

“It doesn’t matter if a student’s first language is Spanish, Creole, Arabic, etc.,” Alexis Susdorf said.

The education department works hard to provide district schools and charter schools staff and students with the support, training and resources they need to be successful, Susdorf said.

Douglas said she believes in the importance of other languages, and refugee students should preserve their heritage, but they should still be proficient in English, the language of their adopted country.

“We have an English-emergent model,” Douglas said. “That is the goal, to help them become proficient in English.”

The superintendent said she wished she had preserved the foreign language she studied in high school. She also mentioned a new program in which students in Arizona will be able to receive a special seal on their diplomas and transcripts when they attain a high level of proficiency in a language other than English. The Arizona Seal of Biliteracy was signed into law in May by Gov. Doug Ducey.

Time and hard work to learn English

It takes three to five years of practice for students to learn basic written and spoken conversational language, Martines said. But it can take up to seven years to learn English at an academic level.

One of her students, 6-year-old Aimable Ngendakumana, spoke only his African language, Kinyarwanda, when his family came to the U.S. from Rwanda. He came to the U.S. when he was just a baby.

“My whole family speaks African at home,” Aimable said. “My mom doesn’t know how to speak English, or my dad. My baby sister doesn’t either.”

He now speaks English without an accent, crediting his proficiency to a great teacher. And Aimable loves sharing his knowledge with other students.

“If they need help to do their homework, I’ll just tell the teacher and I’ll help them,” he said.

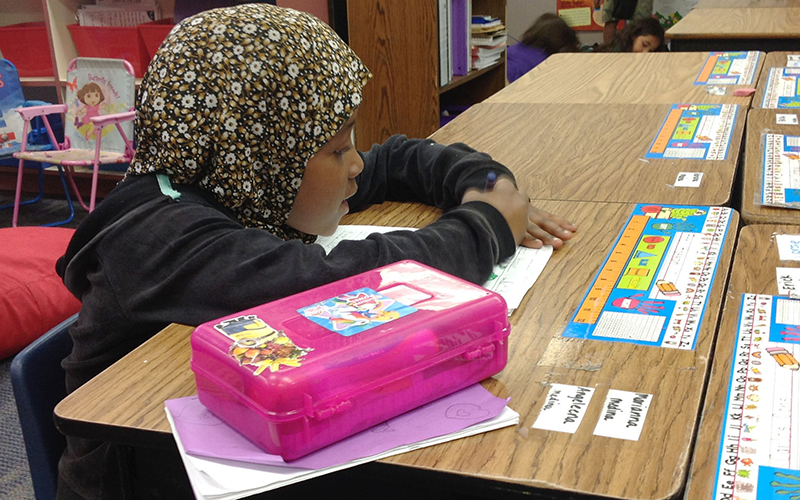

Another of Martines’ students, 6-year-old Fozi Hassan, may soon test out of the English Language Learner’s class. She learned some English from her older brother and sister, but said her parents only speak Somali.

It took time and hard work for her to learn English. She often had to sit behind a computer and repeat words in English as images were displayed.

“They taught me to speak in a complete sentence and I got it,” said Fozi, who now speaks English without an accent.

Arizona uses a program that allows students to be taught based on a measurement of their English language proficiency, ranging from “pre-emergent” to “proficient.”

Besides regular classes like physical education, art and music, ELL students also take four hours of English conversation and vocabulary, reading, writing and grammar. Arizona law requires all instruction and materials to be in English.

“This ensures that all students receive maximum exposure to English during the school day, and this immersion allows students to acquire the language necessary to be successful in academic-content classes,” Susdorf said.

Ten years after coming to Arizona, life is good for 19-year-old Jolie Zuza, her way eased by the communication skills she learned.

She is a freshman at Grand Canyon University, studying health administration. One day, she may return to her home country in Africa.

^__=

Fozi Hassan, 6, is a first-grader at Porfirio H. Gonzales Elementary School in Tolleson, where she is in the schools English-Language Learner, or ELL, program. (Photo by Alejandro Barahona/Cronkite News)

Angelica Martines teaches students in the English Language Learners (ELL) program at Porfirio H. Gonzalez Elementary School in Tolleson. (Photo by Alejandro Barahona/Cronkite News)