- Slug: BC-CNS-Lethal Restraint Superhuman,2100 words.

- 4 photos available (thumbnails, captions below).

By Shahid Meighan, Nathan Collins, Elena Santa Cruz

Howard Center for Investigative Journalism

Deputy Steven Mills of the Lee County Sheriff’s Office was on patrol one night in 2013 when he received a call about a Black man walking down a rural road in Phenix City, Alabama, naked in 50-degree weather.

Mills said the man ignored his calls to stop, but when the officer threatened to use his Taser, 24-year-old Khari Illidge turned and walked toward him, saying “tase me, tase me.” In a sworn statement, the deputy later said he had to tase Illidge twice because he’d been unable to physically restrain the “muscular” man with “superhuman strength.”

“In all of my years as a law enforcement officer, Illidge was the strongest person that I ever attempted to arrest,” Mills said in his statement.

Other officers who later arrived at the scene used the same language in describing Illidge, who a medical examiner said was actually 5-foot-1-inch tall and 201 pounds. They put him in a hogtie restraint – in which the man’s arms and legs were bound together behind his back – and shortly thereafter noticed he had stopped breathing. Illidge was rushed to a hospital by ambulance but was pronounced dead.

Mills said in his statement that he thought Illidge was “under the influence of narcotics.” The pathologist said Illidge’s toxicology report came back negative for any “known” substances. He initially ruled there was no direct cause of death but, after reviewing police reports and body camera footage, blamed the cause of death on “excited delirium syndrome as a result of an unknown substance that he ingested.”

“Excited delirium” is a hotly contested term often used to justify police use of force, historically against Black people, according to law enforcement researchers and experts. The term is not widely recognized by medical associations, including the American Psychiatric Association.

One of the syndrome’s frequently cited symptoms is “superhuman strength.” Used formally and informally in police training, the term creates a hurdle for legal accountability in prosecuting officers, since courts typically defer to law enforcement in determining whether use of force was necessary, according to legal experts.

A review of dozens of police use-of-force cases, including court records, depositions, police statements, and news reports by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University, in collaboration with The Associated Press, found numerous cases where police officers stated that a person who died while being apprehended allegedly displayed “superhuman strength.”

“‘Superhuman strength’ plays perfectly into ‘scary Black assailant,’” says Seth Stoughton, a University of South Carolina law professor who served as an expert witness in the trial of an officer convicted of murder in George Floyd’s death. “It plays into the racist trope.”

The Howard Center sought interviews with the departments and officers named in this story. All but one failed to respond; the Ferguson Police Department noted that the officer in question no longer worked there.

An ongoing trope

Even though “superhuman strength” became widely publicized around the 1991 beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles Police Department officers, its racist origins date to the late 1800s in the Reconstruction era as slavery was abolished in the United States and Black Americans migrated north.

In an effort to stoke fear, white Southerners launched a propaganda campaign that characterized Black men as innately savage, violent and intent on raping white women. Writers and filmmakers used their work to portray Black men as inherently criminal. In the 1905 book “The Clansmen: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan”, Thomas Dixon Jr. depicted Blacks as “half child, half animal.” The novel’s 1915 film adaptation, “The Birth of a Nation” characterized Black men as rapists and beasts and used that trope to justify lynchings while glamorizing the Ku Klux Klan.

The “brute” caricature popularized by such works fueled widespread violence. According to data from the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization that provides legal representation to people illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced, or abused in custody, more than 4,400 Black Americans were killed by lynch mobs between 1877 and 1950. Since not all lynchings were documented, it’s impossible to know the true extent of the killings.

Because of widespread lynchings, assaults, and increasing segregation, Black Americans fled to the North in droves. However, they encountered more racism, segregation, and violence in northern urban spaces as their population grew. In order to enforce tighter control over the population, civic leaders, politicians, and newspapers concocted the image of the “negro cocaine fiend” who was hypersexual, had enhanced physical prowess, and murderous and violent intent.

For example, a 1914 New York Times article written by physician and professor of pathology at the University of Iowa, Edward Huntington Williams, described Black men on cocaine as being capable of other worldly feats, such as surviving potentially fatal gunshot wounds. He portrayed Black men as uniquely violent and dangerous while using the drug and even described that officers in the South began using more powerful guns to “combat the fiend when he runs amuck.”

The Civil Rights era of the 1960s weakened the credibility of the “Black brute” caricature, as national media focused on peaceful Black protesters, many of them women and children, being attacked by police with batons and dogs or sprayed with fire hoses.

But the United States’ “War on Drugs” and its target on communities of color helped resurrect the myth of the superhuman and criminal Black male.

Similar language was weaponized during the crack epidemic that swept the 1980s. Cocaine, and its solid form crack, were intertwined deeply with race. Powder cocaine was more often associated with wealthy Whites, while crack became associated with Blacks, criminality and violence.

The legal system’s perception of crack versus cocaine was reflected in sentencing laws. Federal mandatory minimum laws – a fixed sentence that a judge must impose on a person convicted of a crime – were far more severe for crack, or solid, than powder cocaine.

By the early 1990s, “approximately 93 percent of those convicted of crack offenses were black; 5 percent were white,” author and civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander wrote in “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.”

From drugs to size

After the 2014 shooting of Tamir Rice, a representative from the Cleveland Police Department described Rice as “menacing” and “a 12-year-old boy in an adult body.” Rice’s autopsy listed him as being only 5’5” and weighing 195 pounds at the time of his death.

Similar language was used after the 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Former police officer Darren Wilson said “I felt like a 5-year-old hanging on to Hulk Hogan” when describing the physical struggle with Brown, even though Brown and Wilson were about the same size.

In a 2017 case in Arizona, Muhammad Muhaymin, a homeless man with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, was attempting to use the bathroom inside the Maryvale Community Center when police were called on him, according to records obtained by the Howard Center.

Responding officers ran Muhaymin’s name through their database and discovered a misdemeanor warrant for his arrest. All four of the officers attempted to take Muhaymin into custody by wrestling him to the ground, but noted in their official police statements that the 43-year-old Black man had “superhuman strength” and that his strength was “astronomical”.

One officer even compared Muhaymin to the comic strip hero Superman, even though Muhaymin’s autopsy report said he was 5 feet, 5 inches and weighed 164 pounds at the time of his death, which was ruled a homicide.

The city of Phoenix settled a lawsuit Muhaymin’s family filed against the department for $5 million in November 2021.

“The more Black – if you’ll pardon the expression – someone looks, the bigger people think they are,” said Stoughton, the policing expert and law professor at the University of South Carolina.

A series of peer-reviewed studies published in 2017 in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology looking at racial bias and perceived size found that Americans demonstrated a systematic bias in their perceptions of the physical formidability imposed by Black men. Experts found that Black men were seen as larger, stronger and more capable of causing harm in comparison to white men.

The Social Psychological and Personality Science journal published a similar study in 2015 that evaluated whether white people had a superhumanization bias towards Black people. White participants were found to associate “superhuman” qualities, such as supernatural strength capable of lifting a tank, with Black people more often than they did white people.

“Superhumanization, in our view, is a [form of] dehumanization in a weird way,” Adam Waytz, a corresponding author in the study, said in an interview with the Howard Center. “Superhumanization is treating someone like a non-human.”

This finding can have negative consequences when thinking about how white people perceive the pain tolerance of Black people and how that might apply to real-world interactions, according to Waytz.

Training and the ‘superhuman’

Police trainers say that the perception of “superhuman strength” stems from surprise at unexpected resistance, not commonly seen in training scenarios.

“When you see something that’s abnormal, where a person would typically comply based on an application of force, and they don’t comply, or they seem completely oblivious to pain,” said Spencer Fomby, a law enforcement tactical consultant. “I think that’s where officers start to use that terminology of superhuman strength.”

Fomby has over 20 years of law enforcement experience, having previously served at the Berkeley Police Department in California. He is a national law enforcement consultant and has been a use-of-force instructor for 15 years, specializing in de-escalation, defensive tactics and less-lethal weapons.

But Stoughton, the University of South Carolina law professor, says that training scenarios are typically between two officers and don’t necessarily carry the same implications as the realities of in-field operations.

“Officers don’t actually fight with each other, right? They don’t actually resist each other with strength,” said Stoughton, referring to training exercises.

One California case reviewed by the Howard Center shows that compliance does not always result in peaceful apprehension.

In October 2018, Chinedu Okobi was walking with black duffle bags in his hand when he was approached by San Mateo County Sheriff’s Deputy Joshua Wang, who pulled up next to Okobi in his patrol car. After a brief exchange, Okobi continued walking while the deputy followed him. According to a federal lawsuit filed on Okobi’s behalf, Wang called for additional backup and was joined by four other deputies who descended on Okobi and commanded him to raise his hands in the air, then proceeded to shock the 6-foot, 300-pound Black man multiple times with a Taser.

All five officers then piled onto Okobi as they attempted to arrest him. One of the officers, Sgt. David Weidner, said that they were having a hard time “rolling him over on his stomach” because he had “superhuman strength” – even though Okobi never showed any signs of resistance in dashcam and cellphone video of the incident. According to the coroner’s report, Okobi died from a combination of cardiac arrest following physical exertion, restraint and “recent electro-muscular disruption.” His death was ruled as a homicide.

Frank Rudy Cooper, professor of law and director of the Program on Race, Gender and Policing at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, believes it is how officers are taught to protect themselves that puts them on edge. This fear reinforces the idea that officers are always in danger, which affects how they approach different communities they encounter.

These misconceptions also make their way into the wider criminal justice system. When ‘superhuman strength’ is accepted as a use-of-force justification by judges, the racist narrative gets perpetuated by jurors and in their communities, according to Cooper.

“It is an unfortunate and dangerous thing that the so-called justice system gives a megaphone to those ideas,” says Cooper. “It’s defense through offense.”

According to Cooper, if officers believe that all Black and Brown people might have superhuman strength, they’re always going to be on edge and want to use more force than they need to.

In recent years, George Floyd has become the face of police indifference to Black death. He was a large, Black man who was not resisting arrest – yet was still perceived as a threat. Floyd is just one of numerous police killings, like Khari Illidge, Muhammad Muhaymin and Chinedu Okobi, where the perceived size and strength were used as a posthumous justification for their deaths.

In Cooper’s analysis, Floyd’s demise represents the larger trend of total submission – even death – as the only “reasonable” option.

“That wasn’t long enough, warnings from the medics at about five minutes. That wasn’t enough,” Cooper said. “Nothing was enough until he was dead.”

Reporter Taylor Stevens contributed to this story. It was produced by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Fund in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard. Contact us at howardcenter@asu.edu or on X (formerly Twitter) @HowardCenterASU.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=

Police in Milbrae, California, shock Chinedu Okobi with a Taser after the 6-foot, 300-pound unarmed Black man crossed the street and did not respond to an officer’s question on Oct. 3, 2018. Okobi is one of at least 198 people who died during or after police encounters in California from 2021 through 2021. (Video screengrab courtesy San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office)

Chinedu Okobi lies on the ground in Millbrae, California, on Oct. 3, 2018, after police officers used a stun gun, chemical spray, baton strikes and prone restraint. Deputies with the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office, which provided the video for this still, told prosecutors they were reacting to what they called Okobi’s “superhuman strength.” (Video screengrab courtesy San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office)

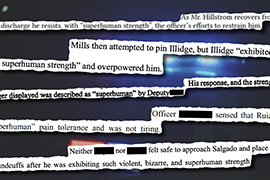

Excerpts from official documents using the term “superhuman strength,” often applied by officers, coroners and prosecutors to describe the force used by subjects during a police encounter. Law professor Seth Stoughton, an expert witness in the George Floyd murder trial, says the term “plays into the racist trope” of a “scary Black assailant.” (Graphic by Jim Jacoby/Cronkite News)

The theatrical poster for “The Birth of a Nation,” the popular 1915 film that has long been denounced for its racist depiction of African Americans and heroic portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan. (Photo in public domain)