- Slug: BC-CNS-Sickle Cell,1430 words.

- 8 photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

By Mia Milinovich

Cronkite News

PHOENIX — Arizona currently has a one- to two-day supply of donated blood, barely half of the standard supply. The shortage is critical for Arizonans who need frequent blood transfusions because they have sickle cell disease.

Sickle cell disease is a red blood cell disorder that affects close to 100,000 Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Sanjay Shah, the director of the sickle cell program at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, said without frequent transfusions, sickle cell patients experience severe pain that can result in organ damage. According to BioNews, simple blood transfusions for sickle cell patients are “typically given in intervals, possibly once or twice a month.”

Tosin Ola, 43, is a registered nurse and the founder of Sickle Cell Warriors, a nonprofit organization that works to share educational resources online about sickle cell disease. She began her efforts back in 2005 with what started as a personal blog, following her lifelong experience with sickle cell disease.

“It’s the worst pain I’ve ever experienced,” Ola said. “Nothing has compared to the pain of sickle cell. It makes you wish you weren’t alive. That’s why people donating makes an impact.”

Blood donation centers like Vitalant urge all people to consider donation, but it is especially important to maintain a diverse blood supply for sickle cell disease patients receiving frequent transfusions. Data from the CDC indicates that sickle cell disease disproportionately affects African Americans, occurring “about one out of every 365 Black or African American births.”

For African American patients like Ola, a specific blood match is critical. Those with sickle cell disease must not only have the same blood type as their donor’s, but antigens in their blood may have to match, too. During shortages, Ola’s blood is flown from the East Coast into San Marcos, California, where she lives.

“There is a reason they’re flying my blood in from Maryland,” Ola said. “Most people that come out to donate are white, but patients like myself are more likely to match with people of African ancestry.”

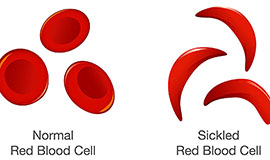

Shah explained that sickle cell disease originates from a variation in hemoglobin, a type of protein found in red blood cells.

“Sickle cell disease is caused by a mutation in the hemoglobin gene that makes the hemoglobin crystallize into long, needle-like structures,” Shah said. “Red blood cells then, instead of being flexible and able to squeeze through narrow spaces, get stuck and break down. That causes obstruction to blood flow and anemia.”

These altered red blood cells can result in pain throughout the entire skeletal system and can eventually impact organ function.

“When you start getting more and more of the adult variety of blood cells, that is when you start getting symptoms,” Shah said. “Then sickle cell eventually affects all the organs.”

For sickle cell patients, transfusions can dilute the amount of sickle hemoglobin in their blood and help them manage their pain level.

“One way of doing transfusions is just giving a small amount of blood as needed,” Shah said. “If you are trying to prevent problems, then you have to decrease the sickle in their blood down to 30 percent or less. For that, they need an exchange transfusion, where you take out blood and give them good blood.”

For sickle cell patients like Ola, blood donation is a crucial part of treatment. Ola’s standard treatment plan, a red blood cell exchange apheresis of six units of blood every three weeks, was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

“After the pandemic, there was a major shortage,” Ola said. “I had to do six units of blood every four weeks twice and attempted six units every four and a half weeks once. I couldn’t survive past four weeks because it was too painful.”

Critical need for blood in Arizona

On Jan. 7, the American Red Cross declared an emergency blood shortage in the U.S. as it reported the lowest number of blood donors in the last 20 years. According to the University of Maryland Medical Center, some of the main reasons why people avoid blood donation include a fear of needles, a fear of feeling weak or fainting after donation and busy schedules that prevent them from showing up.

Vitalant is a nonprofit blood donation organization and a provider for all of the hospitals in Maricopa County, as well as 90% of hospitals statewide. It hosts frequent blood drives, partners with college campuses and has seven clinics across the Valley.

While the status of blood donation has not yet reached an emergency level in Arizona, Sue Thew, Vitalant’s communications manager in Arizona, said the state is still in critical need.

“You can’t wait for an emergency to donate blood,” Thew said. “It is blood already on the shelves that saves people’s lives. It is important to donate on a regular basis to make sure that blood is there for you, a family member or a friend, should they go to the hospital.”

The winter months are a difficult time for blood donations, according to Thew, and are impacted by a variety of factors.

“Teens normally provide one out of every six blood donations,” Thew said. “Imagine the impact that makes when high schools and colleges go on their winter recess. We get an extended period of time where we don’t have access to our largest donor group.”

Not only is the teenage donor pool limited during winter, but blood donation centers must also consider the impacts of the cold season on donor eligibility.

“During winter months, people are more likely to have colds and the flu,” Thew said. “They are not eligible to donate blood if they are showing those symptoms. The … days from Christmas Eve through New Year’s Day were the lowest 10 days of the year for blood donations, which is followed by the highest blood usage month of the year.”

While it is important to recognize the general blood donation needs nationwide, it is also necessary to acknowledge the need for a diverse donor pool.

“The sickle cell gene is postulated to have originated in a malaria-prone area in the equatorial region in Africa and equatorial regions in general,” Shah said. “So it primarily affects African Americans, but it is also seen in Asian Indians, Arabic people and some Hispanics.”

This racial component also extends to current blood donation needs. A critical problem with sickle cell disease and transfusions, according to medical professionals, is that sickle cell patients are more likely to develop antibodies to transfused red blood cells. In turn, those antibodies can result in a delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, in which hemoglobin levels can fall below pre-transfusion levels.

To prevent such reactions, hematologists not only type blood for the four main blood groups but also perform matches against minor antigens, markers that cause the immune system to produce antibodies.

In the case of highly specific blood transfusions, Shah said, the donor pool becomes more limited.

“The propensity to develop antibodies is partly related to the primarily African American recipient pool and primarily Caucasian donor pool,” Shah said. “By increasing racially matched blood, it increases the likelihood of finding the right kind of blood and decreasing the chances of developing antibodies.”

Blood drive

On Feb. 10, Vitalant partnered with the Greater Phoenix Urban League Young Professionals to host a relay for sickle cell, fundraising and drawing awareness for the disease. The event took place at the Paradise Valley Community College in Phoenix, where attendees were encouraged to donate blood at an on-site Vitalant bloodmobile.

John Chavez, 70, was one of the many blood donors at the AZ Relay 4 Sickle Cell event. Chavez said he finds comfort in donating blood to help the sickle cell community, but it also benefits his own health.

“My doctor asked me to donate because I am getting testosterone to help me with my strength,” Chavez said. “He’s recommended that I donate blood every 13 weeks. Apart from my own needs, I like to help other people as well. It can be a lifesaver.”

To help combat the critically low numbers in Arizona, blood donation centers like Vitalant are encouraging all those eligible to consider donating. Ola, like many other sickle cell patients, is dependent upon blood transfusions as a way of life.

“Instead of being trapped in my own body, I can spend time with my children, and I can live the life I want,” Ola said. “We need people to donate because it is sometimes the only way to bridge that gap. There is a never-ending need because we all need life.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=

John Chavez gets his blood drawn in a donation chair on Feb. 10. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

Andrew Fry puts pressure on his arm with gauze after donating blood on Feb. 10. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

Blood collected from another donor on the Vitalant truck on Feb. 10. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

Snacks are kept on the Vitalant truck to help donors recover from blood donation on Feb. 10. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

Tosin Ola founded the Sickle Cell Warriors organization to provide education and resources to fellow sickle cell patients. (Photo courtesy of Tosin Ola)

The Vitalant truck sits on the track during the AZ Relay for Sickle Cell event on Feb 10. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

The difference of Normal red blood cell and sickle cell. (Illustration courtesy of the CDC)

Sanjay Shah, director of the sickle cell program at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, says that sickle cell patients need frequent transfusions. (Photo courtesy of Phoenix Children’s Hospital)