- Slug: BC-CNS-Ethics Board,2260 words.

- 4 photos, chart available (embed code, thumbnails, captions below).

By TJ L’Heureux, Jordan Gerard, Emma Peterson and Anisa Shabir

Howard Center for Investigative Journalism

PHOENIX – In 2021, Diane Mihalsky was so upset by what she saw as the ethical misconduct of a local planning committee member in her uptown Phoenix neighborhood that she filed an ethics complaint with the city. She never learned what became of it, she said.

Jeremy Thacker, a neighbor, filed a similar complaint against the same planning committee member a year later. He had to badger city officials just to get them to acknowledge receiving his complaint, he said.

Phoenix created an ethics commission to enforce the city’s ethics code for its elected officials and employees in 2017. But six years and several ethical controversies later, the city council has failed to put a single person on the commission to enforce the city’s code.

As a result, complaints from Mihalsky, Thacker and other Phoenix residents disappear into a virtual black hole.

Reporters from the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism wanted to learn what other ethics complaints residents or city staff have filed with the city and have gone uninvestigated. In early February, they submitted a records request for every complaint the city had received since the ordinance establishing the commission was adopted.

They experienced the same frustration Mihalsky and Thacker did.

The city did not produce a single complaint by publication deadline, despite sporadic assurances the city’s legal department was reviewing complaints for possible redactions.

Phoenix is the only city among the 10 largest U.S. cities that does not have an ethics board or commission. Annual complaints filed in those other nine cities range from seven per year in San Antonio to over 400 in San Diego, according to their annual filings.

Phoenix officials would not say how many complaints had been filed since the commission was established or respond to questions about how they handle complaints in the absence of a functioning enforcement mechanism.

Thacker’s complaint went to the city attorney’s office, a destination that raises questions about a different conflict of interest.

The city attorney’s office provides legal services to the mayor, the city council, the city’s advisory boards, city manager and departments, according to the city’s website.

That means city attorneys reviewing ethics complaints could be making determinations about the ethical behavior of their clients’ employees.

“A conflict could arise if a city attorney is asked to investigate an ethics complaint related to a matter in which the attorney has also provided legal advice to the city employee or official whose conduct is being questioned,” said Ann Ching, an associate clinical professor at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. “Even in the absence of an actual conflict of interest, the public may perceive an appearance of impropriety if the agency tasked with investigating an ethics complaint is not sufficiently independent.”

In their complaints, Mihalsky and Thacker asked a simple question: Should a member of one of the city’s local planning boards have recused himself from discussing and voting on a rezoning request because he owned nearby properties, some of which he was intending to sell?

Without an ethics commission, Phoenix never answered their question.

Mihalsky’s complaint

Charles “Charley” Jones was a well-known property owner and manager in the uptown neighborhoods of Pierson Place and Carnation when he raised the concern of Mihalsky and Thacker beginning in 2021.

At various times, Jones chaired or was a member of the Alhambra Village Planning Committee, and also held leadership roles in neighborhood associations in Pierson Place. On his company’s website, he listed himself as a member of a neighborhood advisory committee to Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego.

Jones owned 19 properties in the area, many of them rentals.

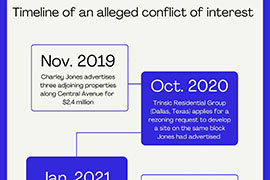

He had commercial interests, too. In late 2019, he advertised for sale three adjoining properties he owned along Central Avenue that later became part of Milhalsky’s ethics complaint against him.

The ad listing the property described it as an “Amazing Redevelopment Opportunity” that could be developed into “Apartment, Senior Housing, Hotels, Retail, Office and more.” The asking price was $2.4 million.

The following year, Trinsic Residential Group from Texas initiated a rezoning request to develop a site along the Grand Canal at Third Avenue, on the same block as the property Jones had advertised on Central Avenue.

Called Aura Trinsic, the proposed development was to have 218 luxury units in a four-story structure, accompanied by a parking garage. The site was two blocks from Milhalsky’s home.

To move forward, the proposal had to go before the Alhambra VPC, which Jones was serving on.

Village planning committees, such as Alhambra’s, are an early step in the city’s rezoning and land use process. Committee members, drawn from the community, have no binding authority but can make recommendations to the city’s planning commission and city council.

As part of their service, VPC members are asked to read through the city’s ethics guidelines. If they have a conflict of interest, they are asked to declare it, refrain from discussing or voting on the issue and file notice of the conflict with the city clerk.

Through a local attorney, Trinsic presented its proposed development to the Alhambra VPC on Jan. 26, 2021. Jones voted for it and did not declare a conflict of interest, according to meeting minutes.

Howard Center reporters phoned and emailed Jones for comment but got no response. In 2021, he told the Arizona Republic that he had no conflict of interest.

In her ethics complaint to the city alleging Jones had a conflict of interest that he should have disclosed, Mihalsky cited an example of a conflict of interest taken from the city’s own ethics handbook:

“The board member owns property in close proximity to property subject to the board’s approval of a zoning or license application that may affect the value of the board member’s property.”

Jones not only owned property near the proposed development but he also had it listed for sale since 2019.

And a buyer was on the horizon at the time of the January VPC meeting.

New zoning sparks second complaint

On Jan. 11, 2021, two weeks before the Trinsic development came before the Alhambra VPC, RAS Development, an established Phoenix developer, incorporated a new limited liability partnership.

The new company was named Forty600 – the same street address as Jones’ property on Central Avenue. In mid-September 2021, Forty600 purchased Jones’ properties on Central Avenue for $2.43 million.

Less than a year later, in August 2022, Forty600 was in front of the Alhambra VPC for an informational meeting about the company’s plans for a new residential and commercial development at the location.

Jones participated in the meeting as a member. Thacker came as a concerned resident; his home would have a view of the proposed development.

During public comment, Thacker pointed out Jones’ conflict of interest with respect to Forty600 because of his prior ownership, according to meeting minutes.

Jones responded that he’d divested himself of the property and therefore had no conflict of interest. He also claimed the city had cleared him of a conflict of interest regarding Mihalsky’s complaint the year before.

That’s when Thacker decided he had had enough.

“I let him have it,” Thacker said.

Two days later, he filed an ethics complaint against Jones with the city.

Complaint languishes

Mihalsky was unaware Phoenix didn’t have an ethics commission when she filed her complaint against Jones in 2021.

She could be forgiven.

While the city has published ethics handbooks for elected officials, board members and commissioners and employees and volunteers on the city’s ethics webpage, the “Ethics Commission” hyperlink leads to a brief sentence about the commission’s responsibilities.

But it does not mention that there is no one on the commission.

Nor does the city’s website provide clear direction on how to file a complaint or where a complaint should be sent.

“I thought there was an ethics commission,” Milhalsky said. “I thought (my complaint) would be investigated.”

Milhalsky continued to fight the Trinsic development as it made its way to the city council. She wrote a letter to the mayor and council in April 2021 opposing the project for how it could impact her neighborhood. She also lamented that the entire process had been poisoned by Jones’ vote on the project.

Jones, meanwhile, wrote the council a letter in support of the project.

In her letter, Milhalsky said she had been told the council would consider her ethics complaint against Jones, but not until a week after the scheduled vote on the Trinsic development.

“I am confounded by the City’s scheduling of consideration of the ethics complaint after the rezoning application,” she wrote. “Charley Jones’ conflict of interest taints the entire proceeding.”

In the end, the council never considered her complaint or relayed any outcome, she said.

“I did not pursue it,” she said.

City’s attorney: no conflict of interest

The city responded to Thacker’s complaint against Jones. It came from David H. Benton, the then-acting chief assistant attorney.

Benton wrote a point-by-point rebuttal of Thacker’s complaint, establishing in legal terms why Jones’ involvement in the zoning application presented no conflict of interest.

“I have concluded that Mr. Jones did not have a conflict of interest,” Benton wrote, “and therefore was not required to declare a conflict.”

The attorney dismissed the example from the city’s ethics handbook that urged an official to declare a conflict of interest if the person owned nearby property, quoting instead a different passage from it:

“Each situation will be decided on the facts and circumstances involved.”

For his analysis, Benton turned not to the city’s ethics code but to Arizona laws governing conflicts of interest.

He concluded that Jones had no conflict of interest because his property ownership could not be considered “substantial and non speculative” under the law.

“Merely owning property in the neighborhood is not enough,” he wrote.

Benton, who has since become the city’s chief counsel, acknowledged that the city’s ethical guidelines were intended to make board members and other officials sensitive to ethical considerations.

But they were not intended to “establish hard and fast rules,” he said.

Thacker later filed a public records request for all complaints made against Jones or his company, Corridor Living, including ethics complaints.

More than 100 days later, the city responded with a single sentence: “There are no responsive final decision or conclusion records as no Ethics Commission has been appointed.”

The experience left Thacker deeply uneasy about the city’s governance.

“I want to move, frankly,” he said. “I’m scared of running out of water, of not having the budget to pay for street and infrastructure maintenance. I think those are legitimate concerns.”

Wrangling over commission drags on

Since Phoenix City Council adopted the ordinance for an ethics commission in 2017, its members have dithered over who to appoint and bickered over whether appointing commissioners would have any impact on enforcing the ethics code.

In addition to the ethics commission, the 2017 ordinance required city officials and staff to disclose gifts worth $50 or more.

The city’s gift disclosure webpage is the only publicly available record related to conflicts of interest in Phoenix.

Between 2017 and 2023, 86 officials filed gift disclosures. Since 2022, only seven did, a falloff that raises questions about how many of the city’s 14,000 employees are actually complying with the gift disclosure.

The Arizona Republic reported that a Judicial Selection Advisory Board had received applications for the ethics commission, interviewed candidates and made recommendations to Phoenix City Council in 2017, according to a former deputy city manager. But the council did not act on those recommendations.

In March 2021, Mayor Kate Gallego created an ad hoc committee to review and recommend commissioners. But when that committee approved the Judicial Selection Advisory Board’s recommendations, Phoenix City Council voted them down. One conservative council member, Sal DiCiccio opposed the commission entirely, while Betty Guardado reportedly voted no because she wanted the commission to have more power.

Public calls for an ethics commission were revived in late 2022 after a controversy embroiled several council members who attended Suns playoffs games and concerts at the Footprint Center in a luxury suite and invited campaign donors.

At the height of the controversy, Mayor Gallego said she planned to bring a vote on the commission between March and the summer break in July.

Gallego’s office did not comment directly to the Howard Center about the timing of a vote.

“Mayor Gallego and city staff are working together right now to put together a timeline and process that is both inclusive and transparent so that the commission has as much support as possible leading up to a vote,” said a spokesperson for Gallego.

The election of Kevin Robinson, who replaced Sal DiCiccio in April, may hold promise for an ethics commission. Robinson told Howard Center reporters he is “a strong advocate for and a supporter of an ethics commission for the city council” and that his office is examining past failures to empanel a commission to determine his next steps.

Mihalsky, a retired judge for the Arizona Office of Administrative Hearings, said the bar for improper conduct is too high without an enforceable ethics code.

“We’re not talking about criminal misconduct,” Mihalsky said. “The main reason there’s an ethics code for people who are making decisions or recommendations on political matters is just so people feel like they got a fair hearing.”

Reflecting on her experience in an interview, Mihalsky said she simply wanted an acknowledgement that Jones’ activity was a conflict of interest.

“Appointed citizens on boards and commissions should avoid this appearance of impropriety,” she said. “You just shouldn’t be making decisions on something that you have a special interest in. It’s really simple. It looks bad.”

This story was produced by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard. Contact us at howardcenter@asu.edu or on Twitter @HowardCenterASU.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=

Embed code for cities chart: <div class=”flourish-embed flourish-table” data-src=”visualisation/14136455″><script src=”https://public.flourish.studio/resources/embed.js”></script></div>

^__=

Phoenix is the only city among the 10 largest U.S. cities that does not have an ethics board or commission. (Photo by Emma Peterson/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

In mid-September 2021, Forty600 purchased Charley Jones’ properties on Central Avenue for $2.43 million. This is the Forty600 lot at Coolidge Street and Central Avenue on Wednesday, April 26, 2023. (Photo by Emma Peterson/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

Construction is underway at the Aura Trinsic development site on Third Avenue and Coolidge Street, seen here on April 26, 2023. (Photo by Emma Peterson/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

Click graphic to enlarge. (Graphic by TJ L’Heureux/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)