- Slug: Sports-Oakland Athletics History Vegas, 2,000 words.

- 3 photos available (thumbnails, captions below).

By Jaxson Webster

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – Oakland Athletics owner John Fisher has his sights set on Las Vegas. And if the team’s relocation comes to fruition, no MLB ballpark will be closer to Phoenix than that one.

On March 4 and 5, the A’s played a pair of split squad spring training games at Las Vegas Ballpark, the current home of the A’s Triple-A Las Vegas Aviators. On April 29, they purchased a plot of land near the Las Vegas Strip.

The A’s rally cry of “Rooted In Oakland” has never been very true, as they are about to pick up their roots and move again.

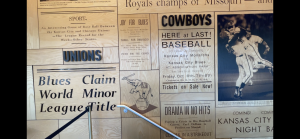

In 1955 the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City. Then in 1968 the A’s moved to Oakland. Now the A’s are planning another move, this time to Nevada. For fans who have long followed this franchise, it hasn’t been an easy road, even though the club’s history is filled with memorable names, include Arizona State products Reggie Jackson, Rick Monday and Sal Bando.

Those long-suffering fans include David Williams, a Philadelphia native born in 1934 whose family owned a candy and ice cream store on Broad Street. He was painfully aware when the team made their first move.

“It broke my heart, I couldn’t picture the A’s in Kansas City,” he said.

A long, trying history

Founded in 1901, the Philadelphia Athletics found true success in less than a decade. To this day their five championships in 1910, 1911, 1913, 1929 and 1930 remain the most of any team to play in Philadelphia.

It’s where Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium, one of the premier lost ballparks of the 20th century, was erected in 1909.

It’s also where the A’s found their elephant logo. Connie Mack, the suit wearing manager of the team from 1901-1950, was “poaching” players from the National League to the American League, New York Giants manager John McGraw has said. McGraw claimed the A’s had a white elephant on their hands, and Mack adopted it as the team’s mascot.

Philadelphia matched the Yankees, winning three pennants and two World Series during a three-year span. The ‘29 Athletics arguably had the greatest comeback in baseball history in Game 4 of the 1929 World Series. Down 8-0 to the Cubs in the bottom of the eighth, Mack’s Athletics rallied and won the game 10-8. They would win the World Series the next night and the Great Depression would hit 15 days later.

They would repeat as champions in 1931 and win the pennant in 1932.

But the last 20 years of the Philadelphia A’s were not as successful.

“It goes back to World War II,” Williams said. “I guess I was a Philadelphia A’s fan because my Aunt Clara must’ve been a Philadelphia A’s fan. In those days they would have Ladies Day, and we would go to Connie Mack Stadium to see the A’s. The thing I liked best of all were the hot dogs.”

By that time the Phillies also played at the same stadium as the Athletics. The A’s had also begun their downfall in Philadelphia. No one told the aging Connie Mack to turn in his suit. He would manage a team that finished in last or second to last from 1935-1946, except for one 5th place finish in 1944.

The A’s were seemingly on the up after they finished above .500 in 1948 and 1949, but 1950 was considered a disaster and Mack’s three sons, Roy, Earle and their half brother Connie Jr., had been given a minority stake of the club and decided it was time for their Dad to step down. The Phillies also won the pennant, cementing themselves as the number one team in Philly.

“I remember being at Lake Harmony, Pennsylvania, listening to the game when Dick Sisler hit that home run,” Williams said, recalling Sisler’s 10th inning home run on October 1, 1950. A home run that propelled the Phillies to the pennant.

“By that time we were starting to move towards the Phillies because the A’s were going to leave and the Phillies won the pennant,” Williams said.

He was right. Roy and Earle shut out Connie Jr. and the Shibe’s attempt to sell the team by mortgaging the A’s to the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company. The mortgage meant the A’s had to pay big money that they couldn’t spend on the team or stadium. In 1954, on the verge of bankruptcy, the A’s were sold to Arnold Johnson. He owned Yankee Stadium and Kansas City Municipal Stadium, where the Yankees farm team, the Kansas City Blues, played.

The A’s moved into Kansas City Municipal Stadium, where they would stay for the next 13 years.

Changing cities

Paul Blackman, a Kansas City lawyer, grew up a Kansas City Athletics fan. He was just 5 when the team moved from Philly to Kansas City.

“I remember the parade in April of ‘55, mobs of people in the streets downtown. This city supported them,” Blackman said.

In their first year in Kansas City, the Athletics broke their attendance record.

Despite the city’s support, Johnson treated the A’s much like the Blues, a farm team. Roger Maris, Cletis Boyer, Hector Lopez, Bob Cerv, Joe DeMaestri, Ralph Terry,and Leo “Bud” Daley, all members of the 1961 World Champion Yankees, had come from the Athletics.

That didn’t deter fans like Blackman from going to the stadium though.

“My parents, sister, and I would go to the game and it was a thrill,” he said. “We’d see the light standards and it was one of the more exciting things going on. We didn’t have the Chiefs yet.”

The A’s had five losing seasons to start their tenure in Kansas City. In 1960, Johnson was at spring training when he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Johnson would pass away and the team was sold to Charlie Finley.

Finley was interesting to say the least. He was first regarded as a hero after adding KC to the hats and jerseys, the first time the A’s had acknowledged, at least on their uniforms, that they had moved west. In 1963 he would change the uniforms all together. Introducing the A’s signature Kelly Green and Fort Knox Gold.

He changed the elephant logo that Connie Mack had made famous and turned it into a mule to represent the Missouri Mule. There was also a robotic rabbit that would deliver game balls to the umpire from beneath the ground behind home plate.

“He brought the Beatles to Kansas City, I’ll give him that,” Blackman said.

That’s about the only thing Kansas City could give Finley though. Finley tried shipping the A’s to Texas, Oakland and to Louisville in the early ‘60s but all were denied. But as soon as the A’s started looking up, they were finally allowed out of Kansas City.

“There were the loveable losers. Kansas City is a great baseball town. Finley made a mistake in my opinion,” Blackman said.

Finley had started building the A’s up with the start of the MLB Draft in 1965, when they took Monday and Bando out of Arizona State. Finley would take a third big ASU star in 1966, Jackson. Finally in 1967, Vida Blue was taken in the second round of the draft, cementing the foundation for Kansas City’s championship A’s.

But just as things were looking up, the A’s moved to Oakland in 1968 and in their first season at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum, finished with an above .500 record for the first time since 1952. This was a odd move to baseball fans because just across the bay, the San Francisco Giants had established themselves as Northern California’s team and the A’s had played less than stellar baseball for nearly four decades. Kansas City would only have one year off of baseball, as the Royals started play in 1969.

“The Bay Area wasn’t an untapped market, the Oakland Coliseum is a horrible place to watch a baseball game,” Blackman said.

Turn of fortune

But A’s fans in Oakland were treated to something special. After Dick Williams was hired as manager in 1971, the A’s became one of the most successful teams in baseball history.

The A’s won back-to-back-to-back championships from 1972-1974, one of four teams to three-peat in MLB history.

“That stuck in our craw a little bit,” Blackman said.

But the A’s success wouldn’t last any longer as Finley was notoriously cheap with his players and in 1976, most of the Oakland dynasty had left to the newly created free agency and through trades.

Oakland stayed at the bottom of the standings for the rest of the ‘70s. It got so bad that at one point only 653 fans showed up to a game in 1979.

Despite their early success, Finley had become uninterested in the team and was looking for a buyer. The A’s were rumored to go to New Orleans, Las Vegas, or Denver but stayed in Oakland thanks to Finley’s wife and a divorce settlement.

Finally, Finley sold the team to Walter Haas Jr., who kept the team in Oakland.

After a reputation as the laughing stock of the league during their rebuild, the A’s returned to prominence in the early ‘80s. Billy Martin created “Billy Ball,” and the A’s would even make the ALCS in 1981, only to get swept by the Yankees.

It would take a few more years for the Athletics to rebuild in the late ‘80s. Jose Canseco and Mark McGwire were led by manager Tony La Russa and would homer their way to the 1988 World Series against the Dodgers. They would lose to Kirk Gibson and his injured left hamstring.

However, they would return to the World Series in 1989, the same season that Mike Selleck, the A’s Baseball Information Manager, started as an intern. He was there when an earthquake struck the San Francisco area and stopped the World Series.

“I was there at the game,” he said. “Heard all the shaking and we thought it was people stomping their feet getting ready for the game.”

Despite the stoppage the A’s would sweep the World Series and for the first and only time, upset the Giants who ruled the Bay Area.

The team would be sold again in 1995 to Stephen Schott and Ken Hofmann, the same year that the Raiders moved back into the Coliseum and constructed “Mount Davis.”

“Not having the open outfield certainly changed the playing of the park. But for most of us it was the great view. That was gone,” Selleck said.

This change also kicked off the Moneyball era, general manager Billy Beane’s strategy of finding cheap and unrecognized players to replace star players like Jason Giambi.

The A’s would lose four straight ALDS Game fives, sprinkled in with a 20-game win streak in 2002, but are celebrated for revolutionizing the way baseball front offices and analytics were viewed.

The team was once again sold in 2005 to John Fischer and a collection of other owners who have built up teams and pulled them back down every three years or so.

“You look at the A’s history and it’s pretty similar,” Selleck said. “Connie Mack had the teams and he had to break them up. Finley did it. Recent years we’ve done it two, three times this century. It’s an all-or-nothing kind of franchise. We got the most 100 loss seasons but the third most World Championships.”

Throughout all this, the A’s have remained in the Oakland Coliseum. After the Raiders moved out to Las Vegas in 2020, the Coliseum became a baseball-only stadium again.

Even before that, the Athletics had been trying to move elsewhere in Oakland. In 2018 they announced their Howard Terminal proposal. MLB said that if the stadium was not built by 2024, they could start exploring other options, which the A’s have done.

Once again, A’s fans have been let down by their city. Three cities have fallen in love, only to have their hearts broken. Could Las Vegas be their forever home?

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.