- Slug: Sports-Don Frye MMA, 2438 words

- 5 photos available

By Andrew Lwowski

Cronkite News

CATALINA, Ariz. – Don Frye eased into his tan leather loveseat with a vibrant serape blanket draped over the back, loosened his back brace and rested a leg on the matching ottoman with a sigh.

Old bullets, his father’s Air Force memorabilia, commemorative Japanese pieces and photos of him and his two daughters fill his living room’s traditional wood shelves. Half a dozen horse saddles are stacked next to his chair and cowboy hats and reins line the wall beside him. Irregular western flagstone paver flooring ties it all together.

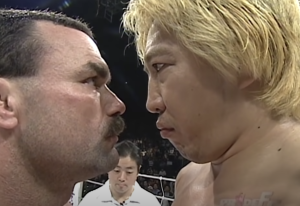

“The Predator,” often regarded as one of the grittiest fighters in MMA history, admitted he hadn’t watched his fight with Yoshihiro Takayama in years. Before the UFC got its legs, Japan’s PRIDE was the top mixed martial arts promotion in the world, and on June 23, 2002, Frye and Takayama delivered for PRIDE 21.

That MMA fight 20 years ago was deemed so great, so fierce that the referee had tears in his eyes, took place. Both fighters exchanged something more than just blows to the face.

“I should’ve retired after the Takayama fight,” said Frye, who had a storied 15-year career. “He stole my soul. I was never the same after that fight. Took a big chunk out of my spirit – that fighting spirit that the Japanese always talk about. I was never the same after that. How do you top that?”

Looking back

Using his TV for the first time since it was given to him while he was in the hospital, Frye, now 56, clicked “play.” A slight smirk appeared through his thick, burly mustache as Takayama – the 6-foot-7, 285-pound Japanese pro-wrestler – and his former self moved to the corner of the ring and exchanged right hands akin to Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots. The match more closely resembled a hockey fight than a professional MMA contest.

“Overall, it’s a blur, but when you watch it, you think, ‘Oh yeah, I remember that,’” Frye said in his distinguished, raspy voice. “He punched me and knocked my feet out from underneath me so I had to grab him by the scruff of his neck to keep from falling. Then we just started punching.”

The fight only lasted six minutes and 10 seconds of the first round, but what had transpired was more than anyone could have asked. “I’m damn proud of that fight,” Frye said. “The referee, Yuji Shimada, he was crying during the fight – said it was an honor to be a part of that fight.”

Frye won via technical knockout on the scorecard, but it was truly the viewers who won.

“Who won?” said Dan Severn, who wrestled and coached at Arizona State where he met Frye. “Well, the audience because they witnessed something that they will probably never, ever witness again. Both men paid a price for that.”

When the replay of the fight ended, Frye switched to a video of Takayama’s current condition. Takayama severed his spinal cord while performing a sunset flip for wrestling for Dramatic Dream Team Pro-Wrestling (DDT) in 2017. The injury left him paralyzed from the shoulders down.

Frye sat in silence and watched the video of what Takayama’s life entails, rewinding and rewatching the move that cost Takayama his body and career.

“Takayama, God bless him, man,” he said. “It’s not fair. He didn’t deserve that. Nobody else on the planet but him would’ve made that fight what it was.”

A tough road

Frye now enjoys a quiet life in Catalina, a rural community 30 miles north of Tucson. He found success in the sport he loved but rooted in that journey was also a dark past.

His mentally of “head down, tail up and charge” drove him to produce explosive combat fights, but what really powered his rage stems from experiences in his youth, and it still fuels him to this day.

Frye was molested three times over the course of his childhood, he said. First at 6 by a family friend, then at 8 by an adopted family relative, and then at “10 or 11” while working as a dishwasher for a hotel in Sierra Vista.

Although Frye and his family fought to press charges, nothing materialized and the experience led to him to start drinking in fifth grade as therapy, he said, before MMA came around.

“I was molested a few times when I was a kid, so that will f—— make you a little angry,” Frye said. “Hell yeah. Hell yeah. It will either make you or break you, and I got lucky – it made me. It gave me something to stay angry about and motivate me.”

Fyre figured the early childhood experience was “just life” as he sunk into a padded wooden chair while rehashing his trauma, staring out the kitchen window at the Catalina Mountains with a cigar in hand.

“I’d like to kill those f—— that did that to me,” Frye said.

That rage followed Frye throughout his career and beyond as he is set to have a “major role” in an up-and-coming movie with actor Michael Paré about tracking down and killing pedophiles, he said. He jumped on the role purely based off the plot, with no monetary motivations, he added.

“I didn’t pick it, it picked me,” Frye said about fighting. “The UFC came around at that time and I was like 28, 29, and then I got into it. I don’t think I fought in the UFC until I was 30.”

When the UFC was started in 1993 – and even up until the early 2000s, it was the wild wild West. There were no weight classes and many of the moves used then are now illegal. However, Frye was a pioneer in the sport, one of the first true mixed martial artists with backgrounds in wrestling, Judo and boxing. His technique would later become the basics of modern MMA.

“The Predator” had a professional MMA record of 20-9-1 with one no contest over his storied career. Although he fought for 11 different promotions, the UFC, PRIDE FC and New Japan Pro-Wrestling were among the biggest.

However, if it were not for Severn, Frye may have never graced the MMA world at all. Severn, who is also a UFC Hall of Famer, is one of only four cage fighters with over 100-career wins, and of those four, only three have over 100 victories. Severn has victories over the other two.

“Dan changed my life,” Frye said. “He got me into the UFC when I asked him to. He got me some fights across the country where I didn’t get paid but that’s pretty much how you test somebody.”

Accomplished career

Ever since Severn coached Frye at ASU, he knew Frye would do well.

“I already knew he had a bone-headed attitude,” Severn said. “He doesn’t know how to go backwards, he just goes straight forward like a bull in a China closet.”

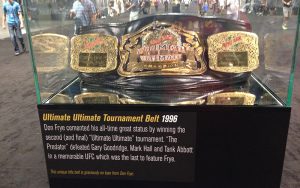

Frye stormed into the fighting scene early, appearing as one of the “most well-rounded fighters” in the UFC at the time, Severn said. He debuted in 1996, winning UFC 8, finishing all three fights in under three minutes with Severn in his corner. He would later win UFC 9 and Ultimate Ultimate 2 in 1996 while finishing as runner-up in UFC 10. At that time, the UFC was set up in a tournament bracket.

Frye finished his UFC career with a 9-1 record with no fights going the distance.

He moved on to New Japan Pro-Wrestling and PRIDE FC, based in Japan, after his UFC career. There, Frye took part in what is known as one of the most iconic MMA fights of all time 20 years ago.

It was Frye’s career and charisma that turned him into an icon overseas. While his close friends knew him as J.R. Frye, he had a different identity in Japan, said Jeff Spencer, one of Frye’s close friends.

“Somewhere halfway between Japan and L.A., he’d turn into Don “The Predator” Frye – rockstar,” Spencer said. “His voice would get deeper, just everything. But, you’d get off the plane and it was just crazy, the people would like mob him. Don being Don, he would take a lot of time with them and I’m sure that’s what made him big over there.”

His popularity also led to his featured role in “Godzilla: Final Wars.”

Before fighting, Frye worked various odd jobs ranging from horse shoeing, firefighting and bartending. But, fighting is just one of the many chapters that altered Frye’s life. The life of fighting – or lack there of – led to a pair of divorces that ended his belief of the possibility of a successful marriage and left him “broke.”

“I didn’t have the money (when I didn’t fight),” Frye said. “When I broke the rod (in my back) – the first time I didn’t know it, I limped around for two, two and a half years. The ex-wife, she’d be loving and caring in front of everybody, but when we were alone, ‘You just aren’t the man you used to be, not as tough as you used to be, you don’t have the pain tolerance you used to have. You’re not a man anymore.’ Then the kicker was when she says, ‘I don’t think you can provide for the family anymore.’ Ah, OK, there’s the truth.”

Just as it had earlier, the UFC changed Frye’s life once again when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2016. “I was in the toilet mentally,” he said. “My horse had died. I had a beautiful stallion. He had died, then the divorce.”

The induction also got him through a major back surgery, one that left him in the hospital for two and a half months, with most of it being in a medically induced coma from brain hemorrhaging.

An enduring friendship

Since he retired in 2011, he has been in and out of hospitals. Over the course of his career, Frye said he has had “45 or 50” surgeries, and his career started to spiral in the wrong direction when he became reliant on pain medication from his various injuries. The one regret Frye had over his career was not listening to his body. Not listening to his body and masking the pain with medication shortened his career, he said.

“I’ve had like 27 just on my back or related to my back alone. A couple on my hand, couple on this (left) elbow, this (right) elbow, about five or seven on this (left shoulder), about five on this (right shoulder). Like I said, the back is a mess.”

Spencer, a retired Battalion chief for the Frye Fire Department (no relation), has been “like a brother” to Frye for nearly 30 years. Spencer met Frye while Frye worked as a reserve firefighter before making it to the UFC.

“A lot of people that were around Don always wanted something from him,” Spencer said. “When he started getting a little bit famous, everybody had their hands out. Don bought everybody’s lunch, he’s a real good hearted guy, and took care of people. I never did that.

“When he was doing pro wrestling in Japan, he was flying, so I went up there and did all the framing on the garage and put their trusses up and got it all framed in for him. Then, he was asking me how much he owes me, and I’m like, ‘Don, you don’t owe me anything. We’re friends.’ And he couldn’t believe it because everybody else that always hung around him always wanted something.

“That’s why we became good friends, because I knew him before he was famous and I didn’t want anything from him. And it just all worked out. And I get pretty pissed off when people try to take advantage of him.”

Spencer admitted he doesn’t have many friends, and he doesn’t like a lot of people, but Frye has always been there, even during the toughest of times.

“My wife died in 1999,” Spencer said. “And Don was still busy doing appearances, doing acting stuff, and he came down and stayed with me for like a month and a half after my wife died.”

Whenever Frye leaves the hospital, he stays with Spencer in Sierra Vista. And it was Spencer who got Frye’s pit bull, Quinn.

“The most special thing to him is his dog,” he said.

When Don came back from California after his surgery and stroke, he was in a bad place, said Spencer. “He wasn’t doing real good, he was in the middle of the divorce at that time, and somebody had this bulldog that they didn’t want anymore and so he called me and he’s like, ‘Can I bring it home?’ and I’m like ‘Yeah.’ Swear to God, as soon as that dog got here, Don started getting better.”

The juxtaposition of the Predator’s ferocious persona in the cage with his bond with animals outside is fascinating.

“I have never seen anything like it,” Spencer said as he recalled a story about Frye. “We were out at one of my friend’s house and there was this horse – we were on this 10-acre thing, and it was on the other side – Don calls over to the horse and the horse comes over and lets Don pet him. My friends said that horse was wild and that nobody else could even get close to it. He’s like an animal whisperer or something, he has something special with animals.”

Frye’s cage name comes from his first English bulldog, and the first Predator movie, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The life of a UFC Hall of Famer has sculpted Frye’s life and perception from when he started, from divorces to injuries to making a living; he admitted he’s “a lot darker now.”

“You get ripped off for a few million dollars, betrayed and lied to and all that, it will change your opinions on a few things,” Frye said.

But at the end of the day, he doesn’t wish he had it any other way. He lives a simple life on a quaint two acre property backing the Catalina mountains. His pride and joy come from a cigar, his pitbull, Quinn, and two horses, Puzzle and Funk. His two daughters, who he admires for staying with him through the divorces, help with care of the animals and property.

“Don Frye is a guy who enjoys his life,” Frye said. “Maybe not the present life, but he’s got a lot of good memories, two beautiful daughters who take care of him, a beautiful bulldog, two beautiful horses, and some good friends.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.