- BC-CNS Japanese Incarceration Photo Essay. 600 words. By Alex Gould.

- 8 photos and captions below.

- Audio clips available.

- Video available.

By Alex Gould

Cronkite News

SUN CITY – President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, setting in motion the incarceration of more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent during World War II.

Eighty years later, Richard Matsuishi wants America to know about this stain on U.S. history so that such imprisonments will never take place again.

EO 9066 authorized the secretary of war to use his discretion to remove and relocate all people deemed a threat to national security to “relocation centers.”

Matsuishi was just 4 when he and his family were forced from their California home and sent to the Poston War Relocation Center near Parker, which is along the Colorado River in western Arizona.

“It was a sad chapter in the history of the United States and probably the worst decision that was ever made by the United States Supreme Court – declaring that Executive Order 9066 was constitutional,” said Matsuishi, who now lives in Sun City.

Nowhere did the order explicitly say “Japanese” people were the target – and some European refugees were incarcerated on the East Coast – but it was clear when the War Relocation Authority was founded a month later.

The authority “formulated and executed a program for removal, relocation, maintenance and supervision . . . of persons (principally of Japanese ancestry)” across 10 interior relocation centers in the U.S., according to the National Archives.

Two of the 10 facilities were in Arizona: the Poston center and the Gila River War Relocation Center southeast of Phoenix.

The confinement camps had schools, farmland and work facilities, though jobs only offered meager pay.

Life at Poston was “pretty harsh” Matsuishi said. The confinement camps were surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards who were ordered to shoot anyone attempting to escape. The Japanese Americans incarcerated there tried to establish a sense of community by forming schools, police forces, churches and more.

Living conditions and amenities were spartan. Matsuishi recounted having a cyst lanced at a medical facility that was barely more than a clean barrack.

Each of the barracks were divided among as many as five families. The barracks had one light bulb and an oil-burning stove that provided heat, but there was no air-conditioning or evaporative coolers.

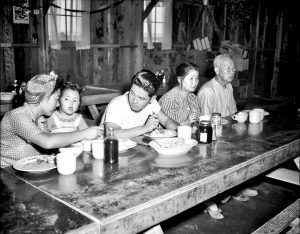

People at the confinement camps ate in mess halls similar to those on military bases, and they were required to eat in shifts.

The U.S. government released propaganda videos that showed smiling Japanese Americans boarding buses to go to the facilities.

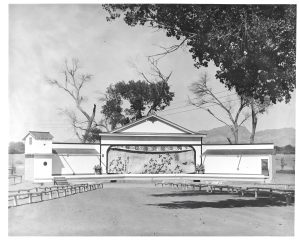

Despite the harsh, forced conditions, incarcerated Japanese Americans attempted to create a community behind the wire, building outdoor stages, baseball fields and other facilities.

Two-thirds of those incarcerated under EO 9066 were U.S. citizens forced to relocate by their government because of their Japanese heritage.

“They claimed that the Japanese Americans are doing their patriotic duty for the war effort by voluntarily assembling and going to these camps,” said Karen Leong, an associate professor of women and gender studies and Asian Pacific American studies at Arizona State University.

Most of the people who were incarcerated at the confinement camps have died, but those who remain are dedicated to ensuring something like this never happens again.

Japanese Americans were finally allowed to return to their homes beginning in 1945, with the last confinement camp closing in March 1946, according to History.com, but some found their houses and belongings had been sold for “failure to pay taxes,” and many continued to face discrimination.

In 1988, President Ronald Regan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which provided the remaining survivors a written apology and $20,000 in restitution.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.