- Slug: Sports-Sustainability Name Rights, 1,064 words.

- File photo available

By Henry Greenstein

Cronkite News

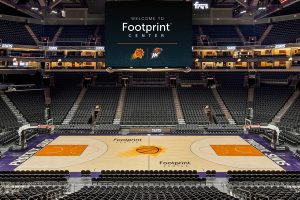

PHOENIX – For Phoenix Suns fans immersed in the high drama of the NBA Finals, the decision might have come as a surprise. The team announced on July 16 its intention to rename the downtown arena to Footprint Center, after local plant-based packaging company Footprint.

For experts on sports business, and its intersection with environmental issues? Not quite as shocking.

“When you (a team) add some type of sustainability component or climate component, it gives you an opportunity to say that you’re actually sending a very positive message,” said Rich Brand, a sports lawyer at Arent Fox who frequently negotiates naming rights deals, “at the same time that, you know, admittedly, you’re getting paid a little bit of money here and there – or a lot of money here and there.”

Brand represented Amazon in its $300-$400 million deal to rechristen the home of the Seattle Kraken and Storm Climate Pledge Arena, after Amazon’s initiative urging companies to substantially lower their carbon emissions. That environmentally focused agreement in June 2020 was followed by Ball Arena in Denver in October and now Footprint Center< in Phoenix.

Both Ball, with aluminum, and Footprint, with plant fibers, are focused on reducing plastic waste.

These naming rights deals show sustainability-focused companies rising to new levels of prominence in the sports world, through “a sponsorship agreement on steroids,” as Brand puts it, and increasing their public reach.

“I think it shows the maturity of the movement – environmental sustainability movement – whether it’s a consumer product or not, to be able to have the resources to position itself,” said Brian McCullough, a sports management professor at Texas A&M University who specializes in sport ecology.

What’s more, McCullough’s research at the Special Olympics in Seattle found that when fans partake in environmentally friendly practices at sporting events, they bring these back to their home communities, and “even fans that might be reluctant in their everyday life would actually engage in those behaviors,” he said.

This aligns with one of Suns owner Robert Sarver’s goals with the Footprint partnership, as stated in a press release: “Integrating Footprint’s plant-based fiber technology into our core business functions will mobilize partners and fans to drive collective and systemic change, in our arena and beyond.”

Kristen Fulmer, founder of the sports sustainability agency Recipric, noted that sports teams have a unique ability to positively influence fan behavior in this domain. She drew a comparison to the Washington Nationals’ partnership with True Made Foods to bring healthier ketchup to their stadium.

“Because the team has done it, (fans are) probably more likely to recognize that label in the grocery store and buy it themselves,” Fulmer said. “So it’s almost facilitating environmental actions, because we know fans are so loyal to their teams that that trust is gained almost immediately.”

Fulmer added that sports help bring environmental discourse to the mainstream. For example, Climate Pledge Arena, she said, generates discussions about sustainability that certainly wouldn’t happen otherwise.

“If someone just describes where they want to meet someone, they have to use the word ‘climate,’” she said. “And so it just becomes more ingrained in our everyday language.”

McCullough noted that naming a facility after a sustainability-focused company does set the bar extremely high for in-stadium practices. (The official press release declared the arena an “immersive living innovation lab.”) He said it will be key for the Suns to carefully consider the totality of their environmental strategy to ensure they’re meeting expectations.

“Research would say that (waste management) constitutes anywhere from four to maybe seven percent of the carbon footprint of an event. So it’s still quite low,” McCullough said. “I mean, it’s still meaningful, but it’s still low in the grand scheme of things. So hopefully, you know, the Suns are doing more beyond that.”

If waste management is only a small portion of a stadium’s environmental impact, why has it been the focus of two recent naming rights deals? Kristin Hanczor, senior partnership manager at the Green Sports Alliance, said it’s more visible to fans than other sustainability efforts.

“You don’t necessarily know how much water is being used to manage the field or how much energy is being used to cool the arena,” she said. “Those aren’t numbers that a fan will come in and see: ‘Wow, this venue’s energy bill is really high, they should be implementing energy efficient appliances.’

“But when you’re a fan, chances are you walk into that venue, you consume something that is going somewhere after you leave.”

Brand said the world is placing an increasing emphasis on what companies like Ball and Footprint do, and (as Fulmer said) naming rights provide them an opportunity to demonstrate their products’ benefits in-stadium. He compared it to his work on the Golden 1 Center naming rights deal with the Sacramento Kings. In the stadium, he said, people who became members of Golden 1 Credit Union got special discounts and fast-pass lanes.

Similarly, Ball can physically hand out its aluminum cups at Nuggets and Avalanche games – as, soon enough, Footprint will distribute its packaging at Suns and Mercury games.

“What better way to get your mission out?” Brand said. “What better way to push the climate pledge? What better way to talk about sustainability and plant-based products?”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.