- Slug: BC-CNS Technology and COVID, 960 words.

- 1 photo available.

By Claire Spinner

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – From adapting robots to decontaminate surfaces and deliver food to developing kiosks that can measure vital signs, experts across the globe are using innovative technology to solve complications brought on by COVID-19.

In Arizona, the push for new technology has led to innovations to help curb loneliness, improve access to health care and track the spread of the disease.

Cronkite News spoke with three trailblazers whose creations aim to solve problems magnified by the pandemic – or which could help tackle another crisis down the road.

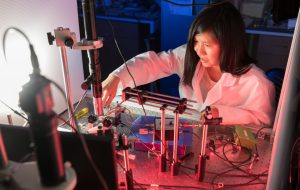

Judith Su’s Little Sensor Lab

Could a handheld device one day detect COVID-19 and other diseases just from the breath? That’s the hope of Judith Su, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Arizona.

Her Little Sensor Lab is working on ways to detect trace amounts of biomarkers for diseases, including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, Lyme disease and COVID-19, which is caused by a virus.

The lab specializes in using optical sensors for ultrasensitive medical diagnostics, employing the same kind of science that allows an Apple Watch to monitor your heart rate or a pulse oximeter clamped to your finger to measure your blood oxygen content.

The technology Su is developing is called FLOWER – short for “frequency locked optical whispering evanescent resonator.” What makes FLOWER different is its ability to detect substances down to a single molecule, using tiny light waves that are about the size of a grain of salt. If the molecule under scrutiny is present, it changes the light’s index of refraction.

“If you can detect lower concentrations of biomarkers, you can get earlier disease diagnostics,” said Su, who last fall received a $1.8 million grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to further research at her lab.

The goal is to create a handheld “point-of-care” device that would allow users to screen themselves for COVID-19 or other diseases by having them breathe into the device.

“This optical technology is something that could immediately improve the quality of people’s lives and really make a difference,” Su said. “It was a no brainer for us to apply it to the pandemic situation.”

The technology also can be used to test out drugs and treatments, something that could be invaluable to the current pandemic or future crises.

“The medical field is something that we can have a lot of impact on, even immediate impact,” Su said. “There are a lot of applications in our lab that we are looking at.”

Cindy Jordan’s Pyxir robotic companion

While much of the technology being created around COVID-19 focuses on physical health, Pyx Health in Tucson is exploring some of the mental health issues that have surfaced, specifically loneliness and social isolation.

Since the pandemic was declared a year ago, researchers have been examining its effect on loneliness and social isolation. One report released in October by the AARP Foundation and United Health Foundation found two-thirds of U.S. adults were experiencing social isolation. Almost a third of adults reported going one to three months without interacting with anyone outside their home or workplace.

Social isolation has been linked to increased risks of dementia, heart disease, stroke and premature death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pyx is looking to help, with a mobile app that uses artificial intelligence to assist people who are especially vulnerable. The app features Pyxir, a “carebot” that can provide 24/7 companionship and support. It helps screen for loneliness and determines whether a user needs human contact or additional resources.

“It’s a little counterintuitive to think that we are going to use technology to solve loneliness, but it is incredibly important because loneliness is so pervasive that you need a scalable solution that people can use in the moment,” Pyx CEO Cindy Jordan said.

Jordan designed the app to be nonclinical, she said. Users won’t be asked for specific information related to physical health. Rather, the robot learns how to treat a person emotionally, based on what the user shares, making each experience unique to the individual.

“If we are going to ask people to engage in a platform, it needs to have a personality, it needs to be a humanlike experience,” Jordan said.

Khalid Al-Maskari’s COPE-ing plan

When the pandemic struck, staff at COPE Community Services in Tucson quickly discovered they were underprepared to make the transition to remote services. The nonprofit physical and behavioral health organization, which staffs about 500 people, needed outside help to keep serving its 15,000 clients.

COPE turned to Health Information Management Systems, a health technology firm with offices in Tucson and Phoenix, to help it quickly move to remote services and launch telehealth options.

CEO Khalid Al-Maskari worked to ensure that laptops were distributed to COPE employees while his team created a remote server to speed and ease functions. Within days, training programs for telehealth services were underway.

Al-Maskari and his team also created an app to help COPE’s employees communicate securely online, as well as a website to allow patients to submit information and get connected to a provider in a matter of minutes.

“We want to do everything possible to make sure employees don’t get stuck on the technical side and clients don’t get stuck not knowing what to do next,” he said.

Numerous health clinics nationwide had to close temporarily – and some for good – because of the shutdowns and restrictions resulting from the pandemic. In Tucson, the technology helped COPE not just maintain its client base but see additional people who needed help during the pandemic.

As COPE CEO Rod Cook told Healthcare IT News: “The value of disaster-preparedness, coupled with an in-depth business continuity plan, should not be understated for integrated health care organizations.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=