- Slug: BC-CNS Caregivers and COVID, 1,685 words.

- 5 photos and captions below.

By Lauren Serrato

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – Before the pandemic, Toni Clayton’s days were sprinkled with lunch dates and card games with friends – welcome distractions from the day-to-day management of the debilitating disease that’s ravaging her 93-year-old husband, Royal.

Then COVID-19 shut down the program Royal attended to help manage his dementia. And at 79, Toni has become his 24/7 caregiver.

“That socialization was what was good for him. So by not being able to do that, it has affected him in a lot of ways,” she said. “Being housebound because of COVID, lifestyle has certainly changed for us.”

It helps, she said, “knowing that I’m not alone and other people are going through this.”

“As my husband always used to say: I think I’m in pretty good shape for the shape I’m in.”

Even before the pandemic, the number of caregivers in the U.S. was on the rise. A May report by the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP found that an estimated 53 million people serve as caregivers, up from 43.5 million in 2015.

Most – 89% – are caring for relatives, and the most common problems in those who need help include general aging issues, mobility and Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia.

The job is at once time-consuming and life-altering. Add a pandemic to the mix, with program closures and quarantines limiting interaction, and caregiving has grown even more grueling. People like Toni face increased hours and fewer breaks as they struggle to meet the physical and emotional needs of their loved ones.

“I have to remind myself: I’m a caregiver, but I don’t want it to define me as a person. So I still try to maintain my individuality and make sure I talk to at least one or two people a day,” Toni said, adding that her pre-pandemic outings had helped settle her.

“I love going out and doing different things. And that has not been the case.”

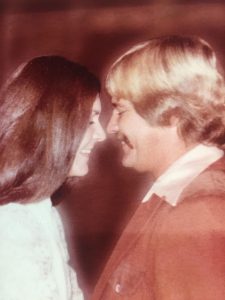

The Claytons have been married for 55 years, and life before Royal’s diagnosis was filled with trips around the world and time spent with their two sons and four grandchildren.

Toni is a retired airline sales account manager and has lifetime passes for air travel. Royal, who served in the Army Air Forces during World War II, was an avid golfer who played some of the world’s top courses, thanks to those passes.

“Our life was relatively normal,” Toni said. “The decline really happened when he started getting weak in his legs. … That was the beginning of a challenge to him, because he wasn’t able to drive anymore and it affected him mentally, and then his mental changes slowly came about.”

Royal was diagnosed with dementia in 2013 – a result, his doctors believe, of a previous stroke. Toni has cared for her husband ever since, but she usually has help.

Before the pandemic began in March, Royal attended programs at least three times a week, for up to six hours a day, at Benevilla, a nonprofit begun in 1981 by Sun City residents to ensure the aging community had support services.

The organization has grown from 30 volunteers offering in-home help to more than 500 volunteers and 100 employees providing a variety of programs for some 5,400 families.

Because of the vulnerable population it serves, Benevilla closed its doors from March 26 through Sept. 14, and has reopened at only a limited capacity.

Among the programs that haven’t resumed is the one Royal attended: Mary’s Place, a day program for those with mid- to advanced-stage dementia. It offered group exercise, arts and crafts, and various brain games to help with cognitive stimulation – all while family caregivers got a much-needed break.

“He’s had a couple of guys that he calls his buddies and his friends, but he hasn’t seen them,” Toni said. “And right now I don’t know if he would even recognize them.”

The population at Mary’s Place is especially at risk during the pandemic, said Lisa Minette, senior director of enrichment at Benevilla.

“We don’t feel that we can keep them safe because they don’t have those boundaries,” she said. “They’re not going to understand why they need to keep a mask on or stay away from somebody or sit 6 feet away – or any of those things.”

To compensate for the loss of in-person programs, Benevilla introduced online sessions, including virtual exercise classes for clients and support for caregivers from trained life coaches.

But Royal, who needs consistency, doesn’t like computers, Toni said, so he hasn’t been taking part. Taking him to a care group at a local church didn’t work either because it was all too different for Royal.

Connie Danks, who helps facilitate the 90-minute virtual caregiving sessions, said that with the extra stressors brought on by COVID-19, caregivers are spent physically and emotionally.

“I had one gal tell me … she was tired inside. It wasn’t just the overall, physical tired,” Danks said. “It was just being so overwhelmed that she couldn’t get her head above water.”

The virtual calls give them a place “to vent and talk and share ideas.”

Danks said one of the toughest parts of the job is witnessing patients experience what she calls the “Velcro syndrome,” when either the caregiver or loved one clings to the other nonstop. She recalled one man who wouldn’t let his wife out of his sight, following her around all day long telling her, “I love you.”

“If she didn’t answer with ‘I love you, too’ he would get kind of hurt and insecure,” Danks recalled. “And the reason he is following her around in the first place is because he’s lost and confused and doesn’t know what he’s doing. And she’s his safe person.”

Toni knows how easy it is to feel disheartened.

“I can’t say it doesn’t hurt when he doesn’t know who I am sometimes. But I realize his brain is not allowing him to rationalize and think about a lot of things,” she said. “When he forgets, he’ll say to me ‘Are you married?’ or ‘What is your name?’ I’ve learned to just answer him and not take it personally.”

Studies from the American Psychological Association have shown that caregivers are at an elevated risk of developing mental health disorders. The loss of therapeutic services during COVID-19 has only made things worse, said Yolanda Garcia, an associate professor of educational psychology at Northern Arizona University.

Garcia is part of a group studying the effects of the pandemic on the physical and emotional health of caregivers. The research focuses on Alzheimer’s caregivers, especially those of Hispanic or Native American descent, and will explore what support resources are available in northern Arizona. The findings will help shape culturally relevant programs.

“Unfortunately, COVID-19 has introduced a virtually insurmountable barrier to meeting caregivers in person – both for service providers and for researchers like us,” Garcia said. “These challenges have left many caregivers without their usual means of support upon which they have relied to relieve stressors.”

Jan Riggs, one of Toni’s best friends, is a caregiver for her husband, Dave. Before Benevilla closed, the women were in the same support group. Now they have periodic, socially distanced wine nights at Toni’s house while their husbands watch Westerns or football.

Jan, 74, became a caregiver to Dave 10 years ago after he was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia, the second-most common type of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease. More recently, her husband, 81, has started to forget their four sons.

“He still remembers me very clearly but other people, he just doesn’t.”

She recalled a day when their youngest son had spent hours playing pool with Dave, who looked at him when they were done and said, “This was really great. Now, what did you say your name was?”

Jan said her saving grace as a caregiver, especially during the pandemic, has been Benevilla.

Dave attends Lucy Anne’s Place, a day program for those with early to moderate stages of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. The program reopened last month, limited to about 30 people who participate in activities in small groups rather than one big bunch.

“When Benevilla opened again, it was like someone reinflated my balloon,” Jan said. “They’re so caring and they make him feel really special. Not only am I free, but he’s in a really good place.

“I’m an extrovert, and I energize by being with people. And I have to admit my patience was really stretched because the conversations (with Dave) were repeated conversations all day long.”

Because the pandemic has forced her and her husband to spend most of their time at home, Jan said, Dave has become her Velcro man.

“He always wants to be attached to me,” she said.

Before COVID-19, the couple enjoyed frequent visits from their sons. Jan said she now struggles to make her children understand the importance of limiting their contact and to help Dave understand why they can’t go out like they used to.

“That’s the hardest thing. Probably every other day he says, ‘Let’s go to the movies’ and ‘Why can’t we go do things?’ To be quite honest, it’s gotten really boring. You can only watch so many videos of Yellowstone and zoo live webs.”

More than anything, Jan said she misses the Dave she married 45 years ago.

“He isn’t there anymore,” she said. “Sometimes I look at him, especially when he’s eating, and it just breaks my heart. It’s the grief, the ongoing grief that is the most difficult for me.”

Toni said she, too, has good days and bad.

“There are days, most definitely, that I get angry,” she said. “There are days I get very, very frustrated. But I don’t let it overcome me. I can’t. … I just deal with it as I have to deal with it, on a second-by-second basis, because I never know what to anticipate.”

Her memories of days gone by help keep her going, through both the pandemic and her husband’s illness.

“We lived a full, abundant life,” she said. “I thank God everyday for the fact that we were able to do that when we were younger. We’ve had some beautiful, beautiful experiences together.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^_=