- Slug: BC-CNS-Refugee Childcare,796

- Photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

By MINDY RIESENBERG

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – Refugee mothers and fathers face various barriers when they arrive in the U.S. with their children.

Finding childcare in order to attend educational classes is one of the biggest issues.

Long wait lists, expensive fees, and the fear of handing their children over to those they don’t know lead many parents – mothers in particular – to skip these much-needed classes on language, finances and job readiness.

Nicky Walker, development manager at the International Rescue Committee (IRC), said the organization noticed there were classes that moms weren’t attending, and realized it was because of the lack of childcare available to them.

“Imagine if a refugee has to leave her kids,” Walker said. “Where will she leave them? With neighbors?”

So last summer, the IRC opened its new Child Watch facility, where parents attending classes can leave their children without worry or cost.

“It’s not easy for a refugee to hand over her child for three hours,” said Aysar Al Khafaji, Child Watch manager. “But when they are brought to the adult classes, the kids are bored, hungry or have to go to the restroom. With Child Watch, they don’t have to worry about the kids while they’re in class.”

Al Khafaji knows first-hand what it’s like to worry about your children as a new refugee. She arrived in Phoenix from Iraq nine years ago with her own two daughters in tow.

“I wanted to give back to IRC since they were my first guide to the U.S.,” Al Khafaji said. “They helped my husband get a job, they enrolled me in a program to become a professional interpreter, and helped me purchase my first home.”

She pointed out that Child Watch gives refugee parents a respite to concentrate on the information they are learning in the classes.

“This is very important because they learn things in the classroom they wouldn’t get right by learning from ‘hearsay,’” Al Khafaji said.

“I used to bring my children with me to the classroom, but they were very disturbing during the class,” said Amira, a mother from Syria with four children enrolled in Child Watch. “I couldn’t continue to attend the classes because I had to stay at home to take care of them. I am really comfortable now taking the classes because they are in the Child Watch program.”

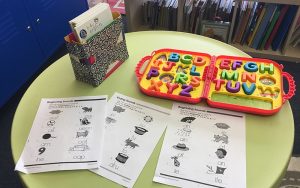

The Child Watch classroom has computers, games, toys, and other educational materials with the children engage. They are taught simple math and English skills, as well as social behaviors inherent to American society, including saying “please” and waiting in lines.

Volunteers from around the world assist Al Khafaji, but everyone speaks English to prepare the children for their new lives in the U.S.

Because many parents worry about leaving their children with people they don’t know, they attend a presentation to put them at ease, explaining the safety and security of Child Watch.

Joy, a mother from Congo who has three children in Child Watch, said she trusts the caretakers.

“I feel emotionally comfortable, and I have no problem leaving my children with them,” she said.

Joy is happy that her children have learned the alphabet, how to write their names, and how to be more organized.

“It is not just a place to play,” she said. “It’s a place for them to think, learn, and become smarter.”

The parents also do better when they don’t have to worry about their children. According to IRC, tests have shown a 20 percent increase in scores in the adult classes once parents have put their children in Child Watch.

Amran, a refugee from Somalia, said her four children have become more social by being enrolled in Child Watch.

“When my children came to the program for the first time, they were shy and didn’t talk, but now they talk and meet new people,” she said.

Al Khafaji is committed to Child Watch because of its focus on children.

“We always take care of the parents,” she said. “Case managers, employee specialists – they are there for them. But what about the kids the first couple of months that they are here?

“Many of these children may have come from a place where they don’t know what’s going to happen next,” Al Khafaji said. “We give them a routine, which makes them feel more safe and comfortable. Every human being wants to belong, and we help them.”

^__=