- Slug: BC-CNS-Bisbee,1,663

- Photos available (thumbnail, caption below)

By DIEGO MENDOZA-MOYERS

Cronkite News

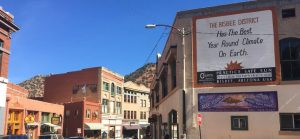

BISBEE – It’s a sunny and cool early February day. The chill in the air perfectly offsets the sun’s glow, heating the canyon that cradles the town. This community, tucked up in southeastern Arizona’s mountains, curls around a massive, defunct open-pit copper mine that once fueled its economy.

Bisbee is a place like no other. Its roots form a twisted combination of an old West mining town and a counterculture haven. It is described politically by Mayor David Smith as “a blue dot in a sea of red,” referring to the strong left-wing politics of the town surrounded by rural, conservative areas in a strongly red state.

After nearly four decades since the “newcomers” began coming to Bisbee – artists, hippies and others looking to escape traditional society’s sphere of influence – a unique culture has formed that is both laid back in nature, but defiant to traditional governance.

“We don’t like to have people walk on us,” said Tom Wheeler, a former councilman and mayor.

To get to Bisbee proper, drivers pass through the “time tunnel.” It’s a lengthy passage that slices through the mountain in which locals say you go in on one end and come out the other in a different period of time.

“You come through the tunnel,” Wheeler said, “and it’s like my good buddy said: ‘Bisbee, Arizona, is 100 miles and 300 years from civilization, nestled into the crotch of the Mule Mountains, 85603.”

Nestled along the border, it’s also here that President Donald Trump plans to build a wall and continue a crackdown on immigration, something Smith says is “ridiculous, and totally blown out of proportion through ignorance.”

Other long-time Bisbee residents say the wall is a waste of money.

“We tend to be closer to our neighbors in Sonora, so therefore there is more of an anti-stance on walls and borders and things like that than elsewhere in the state,” Smith said. “The presidents [of the U.S. and Mexico] may disagree, they may call each other names, but at our level it’s really important. We’re the ones that interact with each other, and we don’t have to use politics to play games.”

Just as it was the first town in Arizona to legalize gay marriage and to ban plastic bags in grocery stores, Bisbee has long gone against the political grain. The small community of around 5,500 people takes pride in being politically active, but at times Bisbee has been quieted within the state’s discourse.

“Bisbee doesn’t get to participate in national offices too much because it is rather different from the rest of Cochise County,” Smith said. “Cochise County is ranchers and [people] like that, which are traditionally conservative. So, we have this group here that is very liberal, but it continues that Bisbee doesn’t get to have its voice heard because it doesn’t match the other areas of the county, which really control the votes.”

Faye Hoese, a community activist and resident since 1974, said political involvement has increased over the past 20 years; more so lately given the heated political climate.

“A lot of people from Bisbee did the march in Tucson; they take people to the polls,” Hoese said. “Bisbee, politically, mostly the newer population, say that in the past 20 years, they’re much more involved politically than people who were here before.”

This story begins in earnest more than 40 years ago, in what was once a prosperous mining town that quickly became a center for the counterculture movement in the 1970s and early 1980s.

The Copper Queen Mine, then owned by industry giant Phelps-Dodge, experienced a slow decline through the 1970s that led to its closing in the mid-1980s. Property rates fell as minors left town. In came the “newcomers.”

These young people came in and bought property for “literally hundreds of dollars,” according to Hoese, and art galleries sprang up while the town’s music scene became a mainstay of Bisbee culture.

“It became more of an opening of new ideas,” she said.

It was a small-scale ideological revolution that changed the town throughout the 1970s and has lasted to the present.

“They used to say a Bisbee yuppie was someone who had two part-time jobs and a vehicle that runs,” joked Allen Hoese, Faye’s husband, who came to Bisbee in 1975.

The Royale, an old, rich-blue building, sits along the winding roads of Old Bisbee. It mirrors some of the values of the town. It is old but well-kept. If features a stage for plays and shows in one part of the building, a radio station in another part, and a kitchen and small bar that serve free meals three days a week for low-income people who are “food insecure.”

Piano notes flutter through the low-lit dining room of the recently renovated building just before meals are about to be served to the group of people waiting outside. All of the food served is donated by local businesses, and the meals are typically high-quality, multi-course servings.

Dan Maldonado, who runs the weekly meal program, said he hopes this becomes a fixture within the town as a community center.

“It’s an all-accepting community where no one is being judged by how much money they have,”Maldonado said. “It’s a counter-culture statement. People expect and wait for the government to take care of them.

“I’m teaching this community how we can take care of each other. We don’t need help if we think about each other as neighbors in our community. This is a perfect example of that,” Maldonado said.

Such is the nature of Bisbee, a place where community trumps income, and where many of the hippy values of the 1970s continue today, for better or worse.

In keeping true to the culture of defiance, Smith plans to issue a proclamation to Mexican officials later this month in order to reassure them that the recent, fiery political rhetoric and feuding between the two nations’ leaders is nothing more than a political war of words.

“[The proclamation is] talking about wanting to reassure Sonora that we want to continue – and we will continue – not to cooperate, but to share,” Smith said. “We have a common culture and we have a common history. Precisely the reason for the proclamation is trying to reassure the people that we are still neighbors and friends.”

Wheeler joked about how casual relationships used to be with officials from Naco, Sonora, during his tenure as mayor.

“When I was mayor and before, all the mayors around here, every month we had meetings. Different Mexican mayors and American mayors together, we’d go to bars and drink tequila together and sing and have a good time.

“They’d invite you down there and let you stay at their houses,” Wheeler said. “In Arizona, our No. 1 trading partner is Mexico. And we’re doing everything in our power to anger them. I don’t get that.”

Wheeler’s remarks reflect the general feeling Bisbee residents have about Trump’s proposal to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border. Many say the project is a waste of money, and a barrier that won’t stop the flow of undocumented immigrants.

“There’s the old joke that Mexico is going to build a ladder and make us pay for it,” Smith said.

Ranchers in the area, however, complain about immigrants and drug smugglers crossing onto their land. Trump has maintained that building the wall is crucial to secure the border and maintain U.S sovereignty. A U.S. rancher was shot and killed on his property in 2010 by what investigators believe was an undocumented immigrant.

Still, the idea of the wall is not appealing to many of the people in Bisbee. They say Washington’s plan is out of touch with the reality of life along the border.

Many point to the terrain along the border, Native American reservations that span both sides of the border, and also wildlife concerns as issues with building a 20-foot wall along the entire border.

Others, like Wheeler, say they have never had issues when coming across undocumented immigrants. They are often families, he says, not criminals or drug smugglers.

“I don’t know anybody who think A. [the wall] will do any good. Or B, it’s a good idea, or C it’s worth the money,” Faye Hoese said. “Personally, I don’t know anybody who think it’s a good idea or that it will be helpful. Go down to the Naco border, there’s already a big, old huge fence.”

No matter the rhetoric or executive orders coming out of Washington, the town, its culture and its people, high up in the mountains and a stone’s throw from Mexico, are not changing anytime soon.

After coming to Bisbee in 1979, Wheeler, now a fixture in the community, explained that he – eventually – plans on moving out of Bisbee.

“Yeah, as ashes.” Wheeler said, laughter erupting from behind his long, scraggly beard. “After they shake and bake me.”

^__=