- Slug: SPORTS-Trainers Painkillers,1080

- Photo, video story available (thumbnail, caption below)

Eds: This is the third of four stories Cronkite News is moving on the problem of painkiller addiction in sports.

By JONATHAN SAXON

Cronkite News

FLAGSTAFF – Joshua Johnson’s title at Northern Arizona University reads athletic trainer. But he calls himself a “performance enhancer.”

He’s among a new breed of college athletic trainers across the country who have adopted a different philosophy in treating injuries. Their goal is preventing injuries in the first place – and using drugs, long a staple, as a last option.

“The first thing we really believe in is preventative medicine,” said Randy Cohen, the associate athletic director of medical services at the University of Arizona and athletic trainer of the football team. “I think that’s the most important thing. If you can prevent problems from occurring, then you don’t have to deal with them when they occur.”

Johnson is on the same page.

“If you’re able to stay on the field, you’re able to maximize your potential as a student-athlete,” he said. “So that’s our No. 1 goal.”

It wasn’t always that way.

In the early days of athletic training, trainers were more likely to treat players by injecting them with substances like numbing agents for dental surgery to mask the pain and get them back on the field. It was not unusual for players to take the injections without knowledge or education about what was going into their bodies.

“Back in the day, we didn’t do a lot of informed consent with the athlete,” Cohen said. “It used to be, do whatever you can to keep the athlete on the field.”

Johnson added that “when athletic training was kind of born, it was about having someone there who could handle acute injuries and provide medical coverage right then and there.’’

Not any more.

Playing sports can be tough business for the body. Depending on the sport, the near-constant running, jumping, throwing and frequent collisions with other competitors can take a toll on an athlete’s body during a season. Nagging aches and bruises become a new reality for players, and sometimes injuries sustained during the year require rehabilitation during the offseason.

Athletic trainers are responsible for evaluating and treating the injury to the best of their abilities, so the player can get back on the field. In the case of more serious injuries, trainers are also responsible for working with the athlete in recovery and rehab until they are healthy enough to return to action.

Trainers normally work behind the scenes to support their teams and coaches, but they are the first to respond and run to the side of a player who is slow to get off the field after a big hit or to come up lame after landing awkwardly after a jump.

But their work begins long before that.

Before players take the field, today’s athletic trainers put them through a range of assessments such as movement screenings. They assess previous injuries and look for risk factors that can contribute to future injuries. But even with all that information, injuries still happen.

Johnson said a lot of injuries are the result of muscle imbalances that come from repeated actions, like jumping for rebounds on the court or running and cutting on the field. Because of this, trainers look at how a player moves, determine the source of particular muscle imbalances and develop a regimen of exercises to address the injury. Cohen ran through a scenario with the precision of a mechanic analyzing a vehicle.

“If someone has back pain,” Cohen said, “is it because they don’t have enough hip flexibility to get in position without putting stress on their spine versus having good mobility of the spine? So it’s figuring out what is causing it and then fixing that problem.”

When dealing with new, non-catastrophic injuries, the first option athletic trainers turn to for treatment and pain management is not painkillers but corrective and rehabilitative exercise, such as range-of-motion drills and gradual resistance training.

The purpose for the exercises is twofold: exercises that work to directly strengthen the injured area and exercises that also strengthen the muscles that support the injured area to prevent further injury.

“Is corrective exercise a new idea? No,” said Johnson. “But as far as the athletic training realm, I think it’s kind of emerging among athletic trainers in, number one, trying to prevent injury in the first place.”

However, while corrective exercise is almost always the No. 1 option, it may not be the most effective solution for every case of injury and pain management.

“We refer to physical therapy when necessary,” said Johnson. “We have our orthopedics we consult who may be able to offer some insight. Maybe (the team doctor) can provide them with an anti-inflammatory that’s going to help reduce their pain.”

Even though medicine may be used to treat and manage pain, Johnson said the team physician generally tries to avoid using opiates.

“The effects of opiates on the nervous system could have negative effects on reaction time and sports-related skills,” Johnson said. “And the addictive nature of the drug, it’s really not safe for a student-athlete to be taking them on a consistent basis.”

Cohen also favors a more conservative approach than prescribing drugs to treat pain. For nagging pain, he prefers the tried-and-true methods of icing, deep tissue massage and electrical stimulation. He believes long-term dependency on drugs to perform is a sign of a greater problem that has not been addressed.

“We actually use a lot less prescription medication than we have in the past,” said Cohen. “I’m a believer where if you need prescription medications to really be able to participate on the field, we’re doing something wrong in our prevention early on.”

Cohen and Johnson see the landscape shifting toward preventive medicine in the treatment of athletes. While they may not be able to predict and prevent all injuries, they believe a proactive approach is more beneficial to long-term athlete health than sitting back and waiting until a player gets hurt.

“More and more of the preventative,” said Cohen. “Really figuring out how to prevent problems from occurring. And I think the emphasis needs to be on chronic overuse issues, the chronic back pain, the stress fractures.”

And Johnson sees athletic training continuing to change in the future.

“I think it’s just becoming broader. It’s less about acute injury care and it’s more about what can we do upfront to prevent injuries from occurring to begin with. I think that is where athletic training is moving and going, because I think it increases the level of care that we can provide the student-athletes.”

^__=

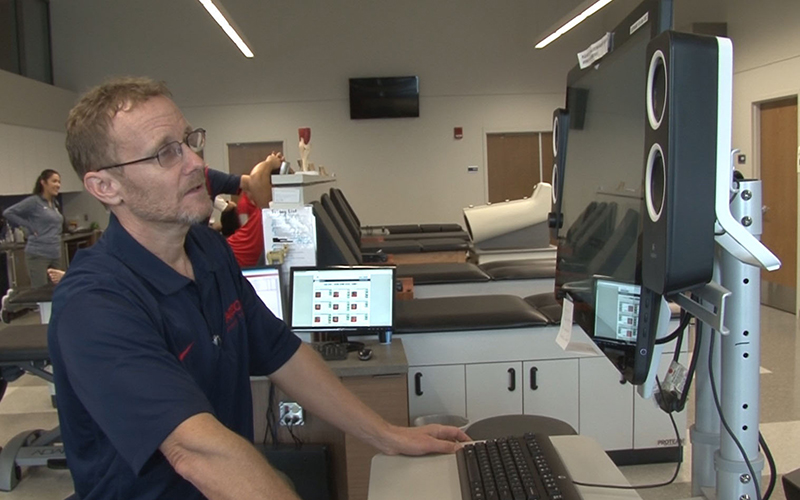

University of Arizona athletic trainer Randy Cohen pulls up a player’s rehab program in the trainer’s room. (Photo by Alex Caprariello/Cronkite News)