- Slug: BC-CNS-Foster Fallout,1280

- Video graphic available (embed code below)

- Photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

By SELENA MAKRIDES

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – Jasmine Flores entered the Arizona foster care system when she was 13 years old. She stayed in the system, moving from group home to group home to group home and changing schools along the way.

As she approached her 18th birthday, she began to think about life outside of the state care system. She’s now 19, the proud owner of a car and a thriving college student, after participating in the transitional programs for aging foster youth.

Flores’s transition story, though, is not typical for the roughly 800 young adults expected to “age out” of Arizona’s foster care system in 2016. There are state programs and charitable agencies aimed at helping youth as they age out of foster care, but only about one-quarter of them take advantage, according to Beverlee Kroll, an independent living and youth services manager for the Department of Child Safety.

“It was easier since I found the resources at the right time. If there are foster kids who don’t know about this program – when you’re 18 you don’t really have any other resources left to go to, all they really help us with is the money,” Flores said.

Flores works for Arizona Friends of Foster Children, majors in business management at Gateway Community College and hopes to open her own salon one day – but that wasn’t always the case.

“It was kind of like a jump to jump to group homes. I’ve been to like, 15 group homes. I went to a lot of different schools, maybe 10,” she said.

Ken Lynch, chief of communications for Tumbleweed, an organization that works with at-risk young people, estimates that 35 percent of the young people his organization serves have left the foster care system “without support, life skills, directly to homelessness.”

DCS has, for several years, faced high numbers of children in state care, low numbers of “case-carrying specialists” and a backlog of inactive cases, according to data from the department, contributing to difficulties for young adults as they age out of the foster care system.

DCS employed 975 active case managers as of June, the highest number since October 2015. Currently, there are more than 18,000 children in state care, up 5.9 percent from the same time last year, part of steady growth since 2010 that originated with the recession and cutbacks to state services.

Doug Nick, communications director for DCS, said that in the past year alone the agency has made significant headway in reversing negative trends within the system. The backlog of cases has been reduced by nearly 60 percent, he said, freeing up case managers to focus on “in the field” work with children.

Most DCS case managers handle “generally speaking, more than two dozen” cases at a time, of varying complexity and need, he said. The turnover rate for case managers hovers near 34 percent, a fact Nick attributes to the demands of the job compounded with a need for better training.

“It’s not unusual to have a high turnover rate in social welfare – no matter what state you’re in. It’s a very high-stress job. We’d like to work on that,” Nick said. “Among the things that we’re doing is to add to our training – how better to do their job, what are best practices. When they feel better-equipped and more knowledgeable, that will help.”

DCS offers multiple programs for children “likely to reach the age of 18,” intended to ease the transition into independent adult life and provide support to newly minted adults striking out on their own.

“After-care” services, as they’re called, cover everything from budgeting and job training to basic life skills like cooking, cleaning and personal hygiene. College-age foster youth have access to Educational Training Vouchers that exempt them from in-state tuition at public universities.

When foster children do turn 18, they have two options.

“In Arizona, you age out of foster care a couple different ways. You may turn 18 and decide you do not want to be involved with this agency anymore and you voluntarily exit services. A youth can sign a voluntary agreement to stay in out-of-home care and participate in services up until their 21st birthday,” said Kroll.

After-care services like the Transitional Independent Living Program and Living Skills Training are contracted out through the Arizona Children’s Association. Young adults seeking to join must “self-refer.”

“A youth who is interested in that service would contract that provider directly,” said Kroll. “They would assign a person who sits down with that youth, talks about what their goals are, talks about what resources they have and depending on what they need, they outline what those services would look like.”

Kris Jacober, executive director of Arizona Friends of Foster Children, said many young people walk away from state assistance in favor of independence, usually leaving them with no family connections and few resources.

“They can’t wait to not be in the system anymore,” said Jacober.

Kroll agreed that foster children often refuse guidance from their case managers, despite being “reminded constantly” of available transitional programs.

“The services are very much underutilized. Part of that is our youth are the same as any other youth. They’re 18 first – they’re not a foster youth first,” she said. “The things we think are important as adults are not always as important to them.”

Of the 800 children who age out every year, only about 200 will take advantage of transitional programming, she said. If at any time former foster care youth find themselves close to eviction, not able to afford groceries or otherwise struggling, they can return to state care until they turn 21.

“They can call whenever they are ready or feel like they need help and say, ‘Hey, I need some help,’ whether it be with getting a job or, ‘I ran out of food and I don’t know what to do,’” Kroll said.

At the Tumbleweed drop-in center, homeless and vulnerable youth can take a hot shower, eat a snack and find temporary reprieve from the Arizona sun. But there aren’t any beds. For that, they are on their own.

”They spend their nights wherever they can. The river bottom is a popular spot. Parks around the valley are also a popular place,” Lynch said. “Anywhere that they can lie down, where they are out of sight, where they feel safe enough to close their eyes and let themselves fall asleep.”

Lynch said that Tumbleweed’s first priority is “their most urgent emotional need, to recover from trauma.” Many children are removed from their homes because of physical abuse, sexual abuse or neglect.

“Because we had parents that care about us, most of us take for granted that we were taught how to wash the back of our neck, wash behind our ears,” Lynch said. “If nobody ever taught you that, you might not do it. That’s the level of neglect we see.”

Tumbleweed supplies 33 transitional apartments in a renovated motel for kids in the most dire need of assistance. In return for keeping their space clean, doing laundry and maintaining a job, the young adults receive all the support they would from their own parents.

Sometimes though, the wounds that require the most attention are internal.

“Even if you’re off the street, you’re getting counseling for your trauma, you’re getting better, you’re able to land a job and now you have an apartment,” Lynch said. “When you close the door, it’s still just you in that room.”

Flores had some words of advice for other soon-to-be adults who may feel they don’t have many options as they graduate from the Arizona foster care system: “Keep trying, because there’s no help unless you look for it.”

^__=

Video graphic embed code: <iframe src=”https://spark.adobe.com/video/HQfgFVkEIaz2r/embed” width=”960″ height=”540″ frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen></iframe>

^__=

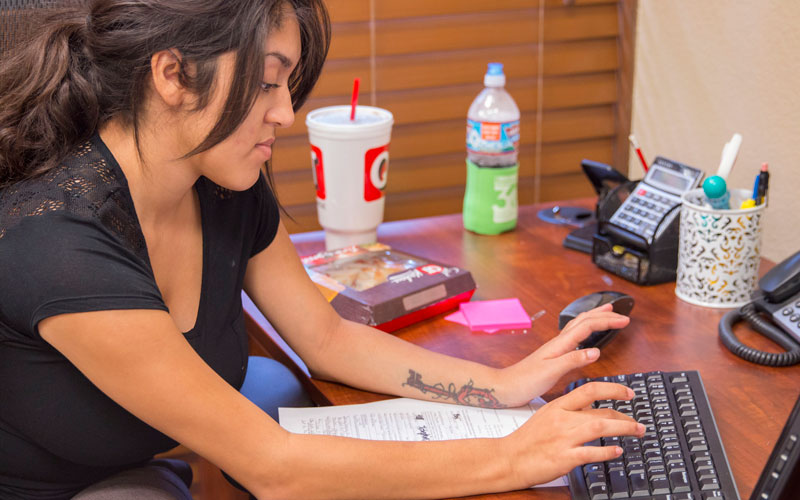

Jasmine Flores works part time for Arizona Friends of Foster Children, the organization that helped her get her GED, her college education and a car. (Photo by Selena Makrides/Cronkite News)