- Slug: BC-CNS Arizona Art Heist, 1,515 words.

- 3 photos and captions below.

- 1 video here.

By Emilee Miranda

Cronkite News

LOS ANGELES – A Willem de Kooning painting stolen from the University of Arizona Museum of Art almost ended up on a wall in a vacation rental, but now it’s back in the public eye for the first time in nearly 37 years.

After a painstaking restoration, “Woman-Ochre” went on display last month at the Getty Center, and it will finally return to Tucson in October.

How this abstract expressionist painting went from damaged goods in a New Mexico estate sale to a masterpiece worth more than $160 million could be the plot of a movie.

De Kooning painted the 30-inch by 40-inch work in 1954 and ’55. It was donated to the university in 1958 by a Baltimore businessman who hoped to create a legacy for his son.

“Woman-Ochre” remained on display until late 1985, according to UArizona, when it was stolen by two museum visitors who slashed the canvas from the frame and rolled it up to hide beneath an overcoat.

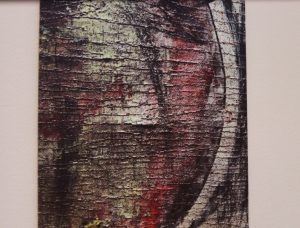

That caused extensive paint lifting and loss. One conservator called the restoration “the largest and the smallest jigsaw puzzle” she ever worked on; another compared the unrestored painting to “a patient on life support.”

No one was ever charged in the theft, which took less than 15 minutes. “Woman-Ochre,” valued at $400,000 at the time, vanished from public view for more than three decades.

The rediscovery

The badly damaged painting resurfaced in 2017 when an antiques dealer in Silver City, New Mexico, attended an estate sale in tiny Cliff.

“When we initially saw the painting hanging in the wall of the master bedroom, behind the bedroom door, we thought it would be a good addition to the artwork in the vacation rental,” said Buck Burns, co-owner of Manzanita Ridge Furniture and Antiques.

He purchased the entire contents of the estate, including the painting, for $2,000 that day. Burns said he had no clue it was a stolen de Kooning until he displayed it in Silver City, where it caught the eye of a de Kooning admirer who insisted it was the real deal. Burns’ associate, David Van Auker, did some internet sleuthing and came across a photo in a 2015 article written by Anne Ryman of The Arizona Republic.

Their immediate reaction was a mix of excitement and terror, Burns recalled. But they knew in their hearts they had the stolen masterpiece – and that it had to go back.

The authentication

Olivia Miller, curator of exhibitions at UArizona, said university officials who inspected the painting in Silver City left it in the frame to avoid further damage by removing it. It was shipped to Tucson still in the frame.

Nancy Odegaard, then head of the preservation department for the Arizona State Museum at UArizona, performed the preliminary authentication. She remembered the painting’s appearance from before the theft.

“I knew it was seriously damaged,” Odegaard said. “I knew that the thieves had done some, I guess, so-called restoration on it. That did not match the earlier reports, but were suggested they were more recent.”

On the back of the painting she found evidence from previous conservation work that she knew had been documented. The age of the wax lining was consistent with what would be normal based on the documents. And the frayed edges of the painting lined up with the torn canvas, sealing the deal for Miller.

“I was pretty well convinced that it was the painting, but after seeing it perfectly line up with its edges, that was really all we needed to know,” she said.

The restoration

The Getty Museum in Los Angeles has a painting conservation department that works with institutions to restore major works of art. The department and the Getty Conservation Institute offered their expertise and facilities to the University of Arizona Museum of the Art for free – on the condition that “Woman-Ochre” be displayed at the Getty until Aug. 28.

The restoration project was expected to take about a year, but the pandemic stretched the project to three years.

The Getty team faced multiple obstacles in making the painting sturdy for travel and display while bringing it close to its original form.

“This was the most fragmented paint surface that I had ever worked on,” said Laura Rivers, Getty associate conservator. “And it was at the same time, the largest and the smallest jigsaw puzzle that I’ve ever participated in, that I’ve ever worked on.”

The team first used macro X-ray fluorescence to learn which paints de Kooning used and how he applied them. The scan revealed that de Kooning sketched in charcoal, but it also showed additional problems for the team: cracks that occurred when the painting was cut from the frame.

After the theft, someone had applied a cheap varnish and used a stretcher to reframe the painting, which caused additional paint damage and tears.

Rivers called the process of reattaching the flaked and lifted areas incredibly painstaking.

“It was carried out under the microscope with tiny dental tools,” she said, “and what’s called a heat pen, which shoots a tiny stream of warm air towards the paint to soften the paint and the adhesive that was used in the lining, which then allowed me to put those flakes of paint back down onto the surface and ensure that they would remain there hopefully for a good long time to come.”

Special solvents removed the varnish and revealed the original surface. Conservators finished by painting in the damaged areas and attaching a new lining, resulting in a painting that’s close to its pre-theft condition.

The heist

Shortly after the UArizona Museum of Art opened its doors the morning of Nov. 29, 1985, a security guard on her way to her station encountered two visitors – a man and woman. The woman apparently started a conversation with the guard as a distraction so her partner could dash upstairs.

What happened to the painting isn’t clear.

“We know it was stolen in 1985, and then in 2017 it was hanging behind the bedroom door,” Miller said. “Anything that happened in between, we can only make assumptions about it because we truly don’t know for sure. Although I think many people would agree it was probably hanging in that bedroom for a very long time.”

The ‘Woman’

“Woman-Ochre” is one of six oil-on-canvas paintings in de Kooning’s “Woman” series, which explores the female figure. When he died in 1997, the Dutch American artist was eulogized as a nearly mythic figure in modern art.

Miller called the work “kind of an alarming painting.”

“It’s somewhat aggressive, and I think for people who really appreciate de Kooning’s work, they have a particular interest in his ‘Woman’ paintings because they are so unique and they are so gripping,” she said.

“For his women paintings, the vast majority of them are not specific portraits. … It’s not as if he was working from a model when he painted a ‘Woman-Ochre’ and was representing a specific woman. These were sort of types or icons, as opposed to being individual portraits.”

The exhibit opened June 7 at the Getty Center in Los Angeles with a private viewing for university officials and others involved in the project.

“You know, this might be a bit of a cliche, but what emerged for me was kind of a medical analogy of a patient on life support, and you and your colleagues in the Getty Conservation Institute, along with the team in the paintings conservation lab, managed to resuscitate this patient, stabilize it, and really bring it back and give it new life,” said Andrew Schulz, vice president of the arts at UArizona.

Burns and Van Auker also attended the private viewing.

“Seeing the painting restored is surreal,” Burns said. “We were up close and personal with the damage. Damage was noticeable even to us, so seeing the painting now shows us what she was, what she used to be before she was cut from her frame all those years ago.

“We are very excited to be at the UofA when the ‘Woman-Ochre’ returns home to the museum in October. ‘Woman-Ochre’ is powerful, and we can’t wait to share her homecoming with our Arizona friends and family.”

The donation

Baltimore businessman Edward Gallagher Jr., a self-described “Sunday painter” who was interested in the newest art in the United States and Europe, donated “Woman-Ochre” to the University of Arizona in 1958, after persuading a gallery owner in Baltimore to sell it to him. It became part of the growing collection he started in memory of his son, who had died two decades before at age 13, according to the UArizona Museum of Art.

“I think for him, when he’s building this modern art collection at this smallish university in the Southwest,” Miller said. “I think he was really thinking about who are the big-name artists doing really interesting work, and how can I get those paintings to the University of Arizona.”

The painting will return to UArizona’s Museum of Art for exhibition from Oct. 8, through May 20, 2023. After that, it will be moved upstairs to the permanent collection gallery, for what Miller hopes is years to come.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=