- Slug: BC-CNS Moms Electric Bus, 1,630 words.

- 5 photos and captions below.

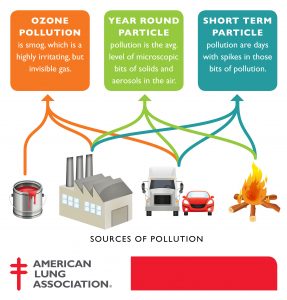

- 1 graphic below.

- 1 video by Twin Rivers School District here.

By Prince James Story

Cronkite News

This story is made possible through a partnership between ASU’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and The Difference Engine, a universitywide center focused on combating inequality.

PHOENIX – More than 4 in 10 people in the U.S. live in neighborhoods with unhealthy air, and the problem affects people of color to a much larger degree.

In one west Phoenix neighborhood, several Latina moms came together to help their kids by targeting the air-fouling diesel school buses their children ride each day.

“It all started because we all want clean air,” said Ana Loaiza-Compean, an organizer with Chispa Arizona, a grassroots organization that works to spark environmental change in Latinx communities.

Years in the making, the mothers’ effort finally saw success this summer, when the Cartwright School District in the Maryvale neighborhood debuted an 84-seat electric school bus – touted as the largest electric school bus in the state – purchased with a bond proposal the moms helped pass.

“A lot of our members are people that have kids with asthma,” said Dulce Juarez, a co-director of Chispa who started fighting for social justice issues as a Dreamer advocating for immigrant youth. “They care about breathing clean air.

“I’m a mom, I have a 4 year old. I want her to breathe clean air.”

A son’s struggles

Loaiza-Compean, mother to two sons and a daughter, is one of the moms who worked on the project. Her sons both grew up with asthma. While the oldest has since recovered, her youngest, 12-year-old Alex, still suffers from the disease, which affects about 6 million kids younger than 18.

“I think he’s going to be an asthmastic for life,” she said. “His symptoms are much worse than his brother’s. His throat closes up, so he has to be on constant steroids throughout most of the year. If he exercises too much, his lungs can’t handle it. It’s been a struggle, to say the least.”

Because air pollution exacerbates asthma, Loaiza-Compean has an app on her phone to track air quality levels every day. On days the app shows green, Alex can go outside and participate in regulated activities. But if the app shows red, she tries to keep him indoors and makes sure his allergy medication and inhaler are on hand.

On the days he’s really sick, she uses a nebulizer to get medication into his lungs more quickly.

“It’s like a war,” she said. “I have to have everything prepped to go to war for the next three or four weeks, because that’s how long it takes for his cough to subside and for his lungs to finally stop being irritated so he can have a semi-normal life.”

In 2019, before the pandemic led to virtual learning, Alex missed about 30 days of school – far more than the 10 usually allowed. Loaiza-Compean had to get documentation from their doctor for the absences to be excused.

Now, she works from home and home-schools Alex, whose condition is all-consuming for the family.

“It affects everyone,” she said. “It affects your budget. It affects your emotional state.

“Alex’s health is always a big deal for everyone.”

‘A slow-moving pandemic’

Ananya Roy is an environmental epidemiologist with the Environmental Defense Fund who specializes in the health effects of air pollution and advocates for more stringent smog and ozone standards, especially in communities of color.

An asthma sufferer herself, she noted that air pollution “is one of the largest environmental threats to health currently,” and then rattled off a series of stunning statistics: “Globally it results in over 6 million deaths per year, and it’s happening year after year after year. So it’s almost like a slow-moving pandemic.”

“It also results in a huge amount of burden in terms of asthma,” she said, noting that up to 33 million asthma-related emergency department visits worldwide can be attributed to air pollution.

“And while you might think that the United States is much cleaner, approximately 100,000 deaths are attributed to air pollution, and nearly 10 to 20% of asthma (emergency department) visits in the country are because of soot and smog.”

The American Lung Association releases an annual “State of the Air” report that ranks states, cities and counties by air quality. Across the U.S., about 135 million people live in places with unhealthy air, and people of color are more than three times more likely to be breathing bad air, the 2021 report found.

The Phoenix area is among the nation’s most polluted cities, the report says, ranking fifth for ozone pollution, eighth for year-round particle pollution and 13th for short-term particle pollution.

Roy noted that although pollution overall is decreasing, “it is going down faster in wealthier communities than in disadvantaged communities.”

“And so there really needs to be targeted solutions that go after reducing emissions and air pollution in these communities,” she said.

One small step

The Cartwright School District is in Maryvale, home to 225,000 residents – 76% of whom are Hispanic. The median household income is less than $50,000, and nearly 40% of children younger than 12 live in poverty, according to the state.

To help this often-overlooked community, Juarez said, advocates worked three years to bring an electric bus home to Cartwright.

A Chispa organizer started attending school board meetings and connecting with community members to plant the seed that an electric bus could help reduce pollution. The group won the support of the superintendent and, eventually, the school board itself.

“We made a case: ‘You have kids. They’re breathing horrible, polluted air from the fumes from the buses, and we need electric school buses. Would you be willing to get one just to test one out?’” Juarez recalled.

With the board’s blessing, Chispa organized a trip with Cartwright’s director of transportation to Twin Rivers School District outside Sacramento, California. In 2017, Twin Rivers was the first district in the nation to deploy zero-emission electric school buses. Its fleet now has 40 electric buses and 37 compressed natural gas buses.

The transportation director began applying for grants to pay for a bus but soon realized more infrastructure would be needed – a charging station, for one. So Chispa stepped back in to organize to help pass a $60 million bond proposal in November 2020 to go toward the bus and other school infrastructure.

Last fall, a group of about 10 moms, including Loaiza-Compean, hit the phones to get voters out.

Erika Cortez was joined by the oldest of her four daughters in making calls for the effort.

“I told all the moms that I knew, ‘Let’s join the group, let’s show support.’ … Those moms would invite other moms, and they would invite others, so we grew,” Cortez said.

“A lot of times, we look at the environment, the place where we live, the ocean and plants, and we think that they will always be there and everything will be fine. We don’t worry about taking care of it so that it all remains there for future generations.

“I think it is extremely important to be aware now.”

There are roughly 480,000 school buses in the U.S., and less than 1% are electric, according to the World Resources Institute, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group based in Washington, D.C.

Transitioning to all-electric buses would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 5.3 million tons a year, according to a report by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group.

Particulate matter from diesel vehicles has adverse effects on everyone, but especially on children with asthma, said Will Humble, executive director for the Arizona Public Health Association.

One issue with diesel buses in particular, Humble said, is the engine idling that occurs when the vehicles are at bus stops or waiting for children to load and unload.

“The kids come out of the classrooms and they’re at the buses and there’s like six buses or something like that, and most districts will just allow the drivers to idle,” he said. “Well what does that do? It means that those kids … they’re sitting in a diesel environment where that diesel exhaust is just accumulating.”

Bill stalled in Congress could help

Replacing old school buses has been a goal across the nation. The Environmental Protection Agency has a webpage dedicated to the topic, noting that students typically ride the bus for anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours each day.

The agency says buses built before 1998 that are used to transport students should be a high priority for replacement, and encourages restrictions on idling, engine replacement and cleaner fuels to help further reduce emissions in newer models.

An enormous infrastructure bill sitting in Congress includes $5 billion to help schools convert to electric and low-emission buses, and dozens of local school board officials from across the nation have called for an even bigger investment: $30 billion over 10 years to “jumpstart the electric transition of the nation’s school bus fleet.”

In the Cartwright district, that transition began June 30, when officials held an event to show off its electric bus, manufactured by Georgia-based Blue Bird Corp.

Today, Chispa Arizona continues to advocate for more electric vehicles across the state, as well as more trees and shade to help combat urban heat islands.

“We always ask ourselves, ‘What is there that I can do for Mother Earth?’ or ‘What is there that I can really do to make things happen?’ With Chispa, I really found a way,” Loaiza-Compean said.

“I don’t see myself doing any other type of work except something that will help our children and help our world and leave it better for our kids.”

Added Juarez: “We all deserve clean air. … We deserve nice and beautiful, clean communities in every part of the state and not just in fancy areas that have all the resources.

“If you care about your future, if you care about kids, if you care about just being alive: Get involved. Take action.”

Cronkite News reporter Ian Garcia contributed to this report.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=