- Slug: BIZ-Insys, 2,200.

- Video story available here

- Photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

- Infographics available below

By JASON AXELROD

Cronkite News

CHANDLER – Insys Therapeutics Inc.’s headquarters lie nestled in an unassuming building complex in Chandler, its only distinguishing feature being the large company logo emblazoned near its roof.

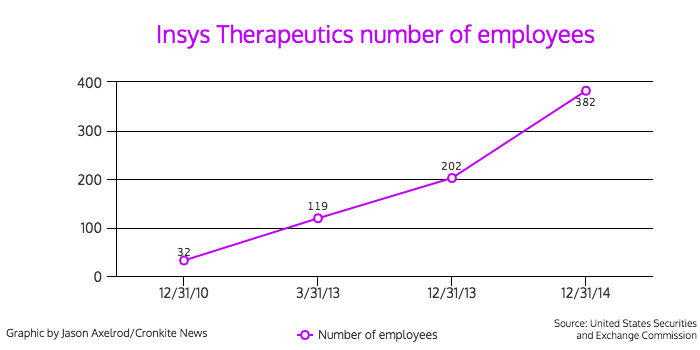

Behind the non-descript façade is a pharmaceutical company that has exploded both financially and in size. The company had a net income of $37.9 million in 2014, and its employees increased from 32 to 382 in four years, according to financial documents.

But the company also faces some turmoil. On Nov. 4, CEO Mike Babich resigned after serving as president for five years and CEO for four-and-a-half. In an earnings call on Nov. 5, Insys founder and chairman John Kapoor said Babich decided to “focus on his family as well as pursue new opportunities.” Kapoor will assume the roles of president and CEO.

The company also faces at least two federal and three state investigations, including one involving the Arizona Attorney General’s Office, according to the company’s U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings. All of the probes are linked to Subsys, a powerful opioid designed for cancer patients already taking similar medications. Insys has noted it is cooperating with these investigations.

The Oregon Department of Justice had accused the company of marketing Subsys for off-label use and improperly compensating doctors for writing more prescriptions for that drug, according to court documents. In August, Insys reached a $1.1 million settlement with the department in which Insys admitted no wrongdoing. The company also has reached a preliminary settlement of $6 million in a class-action lawsuit in which investors accused the company of stock-market fraud.

Han Jiang, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s Eller College of Management, said in an email that Babich’s resignation is a strong signal that the company intends on making changes to remedy its situation.

“Considering the recent awful situation of Insys, such a strong intervention from the owner may indicate that some major changes would be made soon and may help stop the decline and regain market confidence over Insys in (the) short run,” said Jiang, who was traveling to China.

During an interview with Cronkite News in September, Babich acknowledged that Insys was under investigation. However, he declined to provide information on the probes, saying only that the information is publicly disclosed.

“I have to be careful with what we say,” he said at the time.

Kapoor did not return a request for comment.

Rapid financial gain attributed to one product

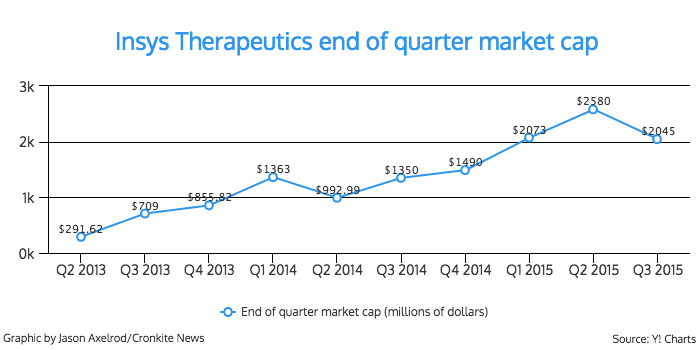

Insys went public in May 2013, and its rapid growth captured local and national attention.

In 2014, the Arizona Bioindustry Association named Insys its bioscience company of the year. Joan Koerber-Walker, the association’s president and CEO, said in a statement at the time that the company’s success was “cause for celebration across the entire community.”

The association said Insys was the top performing initial public offering of 2013.

“Over the past few years, (Insys’s stock has) performed very well,” said David Amsellem, a senior research analyst at Minnesota-based Piper Jaffray. “The company has grown considerably. That’s driven by really one product called Subsys.”

Subsys accounted for 99 percent of the company’s revenue in 2014, according to SEC filings.

Subsys is a spray product that has an intended, on-label use for treating “breakthrough” cancer pain, which the American Cancer Society defines as “a flare of pain that happens even though you’re taking pain medicine regularly for chronic pain.”

Its active ingredient is a highly potent opioid called fentanyl, which was developed in the late 1950s. Venkat Goskonda, head of research and development at Insys, said the company focuses on improving the safety and delivery of existing chemical products, not necessarily developing new chemicals.

“The advantage of going that route is … the development process is much quicker than going into a new chemical entity,” he said.

With Subsys, patients spray a fine mist that contains a small dose of fentanyl onto the thin skin underneath their tongue, which contains many blood vessels. Goskonda said this yields an increased surface area of delivery combined with a fast onset time.

“If you’re a patient suffering from breakthrough cancer pain, the faster you can get pain relief, the better,” Babich said.

For Insys, Subsys also has proven its ability as a tonic for financial gain.

Each Subsys unit contains a single spray, and Babich said that average patients receive between 80-120 units per month. With a single unit costing about $80 (Subsys comes in seven strengths), a patient could pay up to $9,600 for a month’s supply of Subsys.

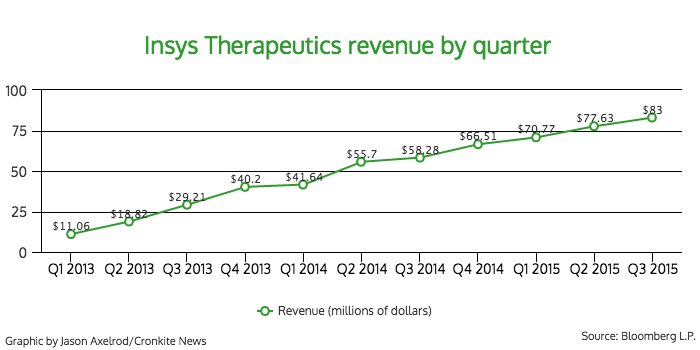

Babich said that last year, Insys earned $200 million in revenue from the product.

In the first six months of 2014, the company brought in $97 million in net revenue. It earned $148 million for the same time period this year.

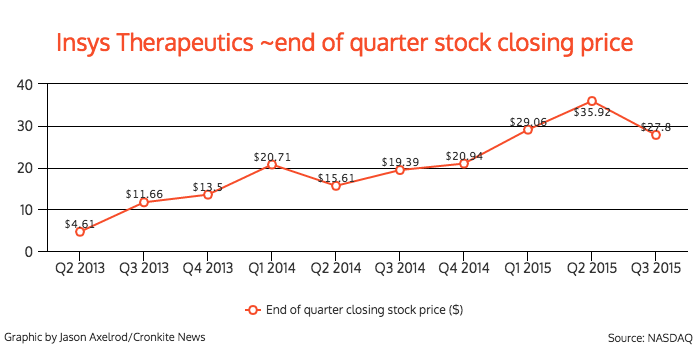

Its stock has seen steady growth as well, peaking at $46.17 on Aug. 3, with a low of $3.10 on May 20, 2013. The company’s stock fluctuated after Babich resigned, and closed at $29.09 on Friday.

CDC: Product’s chief ingredient “a drug of abuse”

Fentanyl, the active ingredient in Subsys, has been linked to numerous deaths.

A study conducted by Alberta Health, the Alberta government’s health system ministry, found that 120 people died in the Canadian province in 2014 after ingesting fentanyl.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that fentanyl “is estimated to be 80 times as potent as morphine and hundreds of times more potent than heroin. It is a drug of abuse.”

Subsys also has been linked to mortality. An analysis of the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System found that Subsys was referenced in 63 cases that resulted in death since the FDA approved the drug in 2012. The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation commissioned the analysis.

However, the foundation noted the report’s limitations: Participation in the FDA’s database is voluntary and the information was sparse.

“It’s reasonable to suppose that a percentage of those prescribed Subsys have cancer and would naturally have a higher rate of mortality,” Roddy Boyd wrote in a Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation article. “ But dying of cancer isn’t usually considered an adverse pharmacological event; dying of respiratory failure when taking Subsys for a migraine is.”

The FDA’s medication guide for Subsys notes that the drug “can cause life-threatening breathing problems, which can lead to death.”

Babich agreed that Subsys is a “very, very dangerous drug.” He cited an FDA program that places restrictions on patients and doctors who use these kinds of drugs.

“It’s very important that the FDA puts these extra hurdles – rightfully so – to get it in the patient’s hands,” he said.

As of January, about 77,000 Subsys prescriptions had been dispensed since the drug was launched in 2012. In its drug category, Subsys made up 40.2 percent of that market share, according to the company’s SEC filings.

Product’s sales practices draw government investigations

The Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts both issued subpoenas to Insys in December 2013 and September 2014, respectively. The human services department subpoena was issued in connection with a U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California investigation.

The offices of the attorneys general for Arizona, Illinois and Massachusetts also are investigating the company. The Arizona Attorney General’s Office declined to comment on its investigation.

These investigations and subpoenas involve either the commercialization of Subsys or sales and marketing practices related to it. Of the company’s 382 full-time employees, 286, or nearly 75 percent, are sales and marketing employees, according to the company’s annual SEC report for 2014.

Earlier this year, the Oregon Department of Justice settled its case with Insys.

The department accused Insys of misrepresenting to patients and doctors what Subsys could be used to treat, promoting Subsys to doctors known to have misprescribed Subsys and similar opioid drugs and making payments intended as kickbacks to doctors to incentivize them to prescribe Subsys, court documents show.

The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research’s FDA-approved labeling guide for Subsys notes that it should be used “for the management of breakthrough pain in cancer patients 18 years of age and older who are already receiving and who are tolerant to opioid therapy for their underlying persistent cancer pain.”

The documents highlighted the company’s efforts to persuade an Oregon doctor – one who doesn’t treat patients with breakthrough cancer pain – to prescribe Subsys.

The department accused Insys of paying $1,600 to a longtime medical acquaintance of the doctor to speak to the doctor about Subsys at a dinner with Insys’ regional sales director. Insys also offered to make the doctor a promotional speaker for Subsys, even though the doctor had never prescribed Subsys. The doctor had told his son that the sales director, who was described in the documents as a “cougar,” had sent the doctor texts proposing “tequila dates,” according to the documents.

Insys had hired the doctor’s son as a sales representative, but the son had no prior pharmaceutical sales or health care experience. The son had texted his father that the company was “relentless” in pressuring him to enroll his father in the FDA program needed to prescribe Subsys. The son resigned from Insys three months after being hired, according to the records.

The labeling guide for Subsys also notes that only oncologists and pain specialists who are knowledgeable about using Schedule II opioids to treat cancer pain should prescribe Subsys. Schedule II opioids — Percocet, OxyContin and Demerol are in the category — are drugs that the DEA deems can be highly abused, which can lead to severe physical or psychological dependence.

Dr. Daniel Malone, a professor at the University of Arizona’s College of Pharmacy and the Zuckerman College of Public Health, said that while physicians may ask about information related to off-label use, manufacturer representatives aren’t supposed to readily volunteer that information.

“They can’t bring it up,” he said. “That would be considered initiating an off-label use, and the FDA would frown on that activity.”

The settlement’s terms stipulate that Insys pay $1.1 million, giving some to the state of Oregon and some to an undefined opioid abuse/misuse prevention organization. While Insys admits no violation of law, the terms decreed that Insys not make any false, misleading or deceptive claims about Subsys in its marketing and promotion of the drug, and that Insys revise its Subsys marketing and sales practices in Oregon, such as its speaker program.

“It is unconscionable that a company would promote such a powerful drug for off-label uses as well as misrepresent to doctors the benefits of the drug,” Oregon’s Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum said in a news release following the settlement.

Malone said this sort of admission without guilt is common for pharmaceutical companies under investigation.

“It’s a risk management strategy,” he said. “Pay a big fine, but don’t actually have the guilty verdict hanging over their head.”

Insys also served as the defendant in a class-action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for Arizona. The lead plaintiff, Hongwei Li, accused the company of making false and misleading claims about its business and making omissions in its public statements, which artificially inflated its securities prices. Li bought Insys stock and claimed to have suffered damages.

Both parties agreed to settle, and in a preliminary agreement, Insys’s insurance carriers plan to pay about $6 million.

Future products show promise

“What makes (Insys) particularly interesting is that it is using its manufacturing and drug delivery abilities to develop a number of other products,” Amsellem said.

One of these products is an improvement on an existing product Insys offers: Dronabinol, or synthetic THC, the active ingredient in cannabis. Insys sells a Dronabinol capsule, marketed as Dronabinol SG or generic Marinol.

Insys doesn’t expect meaningful revenue from that product’s sales, according to the SEC filings. It believes introducing a new oral dropper product, the Dronabinol Oral Solution, will allow it to “further penetrate and potentially expand the market for the medical use of dronabinol,” according to SEC filings.

This oral Dronabinol delivery consists of a dropper patients can use to place liquid drops of Dronabinol under the tongue.

“A lot of times, as you know, patients have trouble swallowing,” Babich said. “So (instead of) giving them a big, thick capsule to swallow, we now have turned the drug into a dropper.”

The FDA accepted the company’s new drug application for filing, and it is set to review and decide on the product on April 1, 2016.

Babich said in September that Insys’s delivery technology showed promise. The company is developing its sublingual – beneath the tongue – spray in other products, its 2014 annual report stated.

“People believe that we can take … different molecules, put them into the spray device and also do some very similar things that we’ve done with Subsys, which are take oral markets and turn them into a sublingual spray market,” he said.

Amsellem said this development pipeline shows financial promise as well.

“There is ample room for significant long-term value creation as the company brings these additional product candidates through development and gains additional approvals,” he said.

That pipeline comes with a price, though. Babich said the company expected to spend between $55 million and $60 million on additional research and development for the idea.

“If we’re able to effectively spend that money over the next number of years and reinvest in the company, we can build a lot more value than we currently have,” he said.

^__=

^__=

Former Insys President and CEO Mike Babich at the company’s headquarters. (Photo by Jackie Padilla/Cronkite News)

Insys Therapeutics research and development analytical scientist Craig Bastian does lab work in the company’s Research & Development Lab. (Photo by Jason Axelrod/Cronkite News)

A single Subsys unit. (Photo courtesy of Insys Therapeutics/www.subsysspray.com)

^__=

Insys Therapeutics:

- Incorporated: 1990 as Insys Therapeutics Inc.

- Number of employees: 382 (as of December 31, 2014)

- 2014 revenue: $200 million